Before Dinner A Short Play by Yasser Abu Shaqra Translated by Faisal Hamadah Arab Stages, Volume 5, Number 1 (Fall 2016) ©2016 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications

Editor’s Note: Before Dinner by Yasser Abu Shaqra was developed, in part, at the 2014 Masrah Ensemble Playwright Residency Program. While the Arabic text is owned by Abu Shaqra, Masrah Ensemble holds the copyright for (and commissioned) the English translation of the play.

Before Dinner

Characters

Nasser

Mother

DJ

Act 1

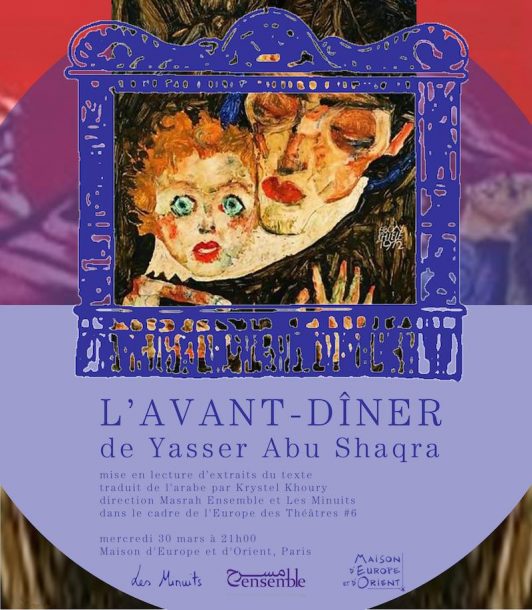

Onstage, a large room. A curtain runs through the middle of the room, partitioning it into two smaller rooms. On the left of the curtain is NASSER’s room. It contains a bed on the left, with a small table facing the audience. On the table there are scattered papers, brochures, a laptop, headphones, ashtrays full of cigarettes, and cups of tea and coffee, some of which are half finished. There are film posters pinned above the bed, and prints by Egon Schiele on the walls. There is a small mirror fastened to the wall near the kitchen door, and a rectangular couch opposite the curtain. On the right of the curtain is MOTHER’s room. It is occupied on one side by a massive, mirrored armoire. There is a bed opposite the armoire. Opposite the two rooms, on the front edge of the stage, is the balcony. In the front corner of the stage, towards NASSER’s room, is the DJ booth, where DJ sits with his gear.

NASSER enters and throws his wallet and belongings down haphazardly.

NASSER: What an honor to have you here!

MOTHER: People usually say “Hello.”

NASSER: Usually?

MOTHER: I mean most people.

NASSER: I don’t remember asking you to clean my room.

MOTHER: I wanted to surprise you. In any case, nobody needs permission to clean up a dump – I’d rather not wait for the maggots to make their way over to my room. I break my back cleaning your mess, and there’s never any praise or thanks at the end of it. When are you going to learn how to be considerate?

NASSER: Praise and thanks, Mother. Praise and thanks … just stop cleaning.

MOTHER: What’s the matter Nasser? You seem on edge.

NASSER: The neighborhood is crawling with security forces.

MOTHER: And? We’ve got nothing to hide… By the way? Where did you get this newspaper? I heard the teachers at school say that this one wasn’t being delivered to us anymore.

NASSER: I delivered it

MOTHER: I’ll go get dinner.

NASSER: Fantastic. I’m dying of hunger.

MOTHER goes to the kitchen to make dinner. NASSER fixes his hair in the mirror. When MOTHER comes out of the kitchen with the food, NASSER goes with her to the balcony. Their movements seem routine and choreographed. After they sit down to eat, the DJ’s corner lights up while the lights on the rest of the stage dim down. Orchestral music begins to play. The scene moves backwards from there until it returns to where it was before MOTHER got up to fetch dinner. The characters’ movements make the viewer feel as if they were watching a rapidly rewound video. The stage goes dark for two seconds, then the characters return to where they were before the dinner suggestion.

NASSER: The neighborhood is crawling with security forces.

MOTHER: And? We’ve got nothing to hide… By the way? Where did you get this newspaper? I heard the teachers at school say that this one wasn’t being delivered to us anymore.

NASSER: I delivered it.

MOTHER: Well, I’m glad you did. I started reading a beautiful interview with Ghassan Massoud in it. He’s your teacher, right? I haven’t finished it yet, though. What do you think of it?

NASSER: Haven’t bothered with it. (Puts on headphones.)

MOTHER: Oh no, Nassoor! You’re really missing out. But why should you miss out, I’ll just read it out loud to you! It’s got the saddest title in the world: “Do Not Kill Us, for We Will Die Ourselves.” She looks over at NASSER, who hasn’t heard. Am I talking to myself?… Nasser… (She yells.) Nasser!

NASSER: (Takes off headphones.) Yes Mother… What is it?

MOTHER: You have me talking to myself like a madwoman, and you have your headphones on! I’m reading this beautiful article out loud for your sake… Pay attention!

NASSER: (Bored.) Okay, fine.

MOTHER: He’s one of your teachers, isn’t he?

NASSER: Nope.

MOTHER: But why not? Isn’t he a teacher at your school?

NASSER: When he feels like it.

MOTHER: Could you at least answer me like a human being? What do you mean “when he feels like it?”

NASSER: I mean … depending on his schedule.

MOTHER: You mean, he might teach you?

NASSER: He might.

MOTHER: You have no idea how proud I’d be … telling everyone that “Ghassan Massoud is my son’s teacher,” and “Nasser’s going to be a big actor when he grows up, like his teacher Ghassan Massoud.”

NASSER: Uhuh … and in the meantime?

MOTHER: Hmm yes… (Continues reading.) “Do not kill us, for we shall die ourselves.” “With his eyes on the television, he follows the reports on the ongoing battle in the town of Kassab. Here, in his home in the Al Malki neighborhood of Damascus, Ghassan Massoud lives out his isolation. ‘Isolation? I don’t think so,’ he says. He qualifies, ‘I live in total alienation. As an actor, I am prepared to work under any circumstances, even dangerous ones. It’s my job, after all – but today on the way to the set, four missiles almost struck my car.’”

NASSER: Nice.

MOTHER: What’s so nice about that? Oh I get it, you mean his way with words. (NASSER laughs.) God help me with this attitude of yours.

NASSER: (Decisively.) I’m listening!

MOTHER: “The Syrian star arranges his articles and thoughts. He pours us a drink, lights a cigar and says to me: ‘I want to say a few words to everyone working in theatre today: Do not kill us, for we will die ourselves.’” What does he mean by that? Aha – “When I press him to elaborate, he insists, ‘I do not want to clarify, but I would like this statement to be used as the title for our interview when it gets published.’”

NASSER: Excuse me?

MOTHER: God – what now?

NASSER: No no, it’s nothing. It’s just that … he’s the one who put the title on the article. (Mockingly.) Poor guy.

MOTHER: Oh, really… This man’s a genius

NASSER: (Lights a cigarette.) There was a glass of shit here somewhere. Where’d you put it?

MOTHER: Watch your tongue… My God, what a foul mouth you have. I washed that glass of … crap and put it where it belongs. (MOTHER continues reading joyfully while NASSER looks around the room for something to drink with the cigarette.) “‘I’ve recently stopped reading about art and culture and have instead chosen to use my time to read about the history of political Islam and the reports released by Western strategic think tanks. I’ve visited many great poets in their homes, and not one did I see with a dictionary in his hand. The same is true of the professional actor who is in control of his tools.’ Massoud is suddenly quiet after glimpsing a headline on Al Mayadeen news channel. The leader of Syria’s National Defense Force has just been assassinated. In silence, he finishes what remains of his Cuban cigar, spewing its smoke to the corners of his house. I find him gazing intently at the painting of Gibran Khalil Gibran that hangs on his living room wall. I read the epigraph on the painting: ‘Woe to the nation where sects and creeds multiply while faith diminishes.’”

While MOTHER is reading the last few lines, NASSER has put the headphones back on and reaches for the bag that he threw down next to his mother. She takes hold of the bag and pulls at it, trying to hold his attention on the last parts of the article. They engage in a tug of war with the bag. The headphones come unplugged from the laptop, and we hear the sounds of porn. NASSER grabs the bag and runs to the laptop while MOTHER is still reading. He switches the sound to a rap song, “Bara’a” (“Innocence”) by Al Taffar. We clearly hear the verse, “Every time the beggars come at your car, turn the sound up, roll up the car window, and post ‘May God be with the poor’ to your Facebook.” Meanwhile, NASSER takes a bottle of beer out the bag and opens it. It explodes all over the place. MOTHER finishes reading and watches NASSER drink the beer and dirty the room in amazement and shock. She begins weeping. NASSER stops the music and sits in front of the laptop.

MOTHER: You’re despicable and shameless. Here I was thinking it was a bottle of cola. Alcohol … in our house, you lowlife. And right in front of me… If you have no respect for me or your Lord, at least have some for yourself. So this is the Nasser that I’ve raised. I can’t believe it.

NASSER: That’s your prerogative, not to believe. You know … I can’t believe it either.

MOTHER: You’re a self-centered brat … and arrogant.

NASSER: Am I? That’s the first time I’ve gotten that one

MOTHER: And mean too. That’s the worst part of it all. You’re mean.

NASSER: Ouf ouf ouf … all this because I’m drinking a beer?

MOTHER: You know, the less we speak the better.

NASSER: You’ve got a point there. That’s the first positive thing you’ve said about me so far. Better not to talk to me. You’re forgiven for all the rest. It doesn’t matter.

MOTHER: What do other woman have that I don’t? All the other mothers have kids that bow at their feet and try to carry their burdens. Or worry about them, at least. I just shaved years off of my life cleaning your room, and you walk in like a spoilt prince.

NASSER: Mother, please, let’s stick to your last point. The less speaking, the better.

MOTHER: Any other commands, your highness?

NASSER: I’m begging you … let’s not speak anymore. I don’t want to talk about anything. I’ll apologize for everything, but please, no more talking.

MOTHER: Hey! How long has it been since we’ve sat down, the two of us? As your mother, I’m in the right to tell you that I’ve missed you and that I’ve missed speaking to you. There’s only a curtain between our rooms, but I miss seeing you. I only seem to catch glimpses of you on special occasions, when you’re coming and going from the house and I’m in the kitchen. (Short silence.) I’ll go get dinner.

NASSER: Great. I’m hungry.

MOTHER goes to the kitchen to make dinner while NASSER fixes his hair in the mirror. When MOTHER comes out of the kitchen with the food, NASSER goes with her to the balcony. Their movements seem routine, choreographed. After they sit down to eat the food, the DJ’s corner lights up while the lights on the rest of the stage dim down. Orchestral music begins to play. The scene moves backwards from there until it returns where it was before MOTHER got up to fetch dinner. The characters’ movements make the viewer feel as if they were watching a rapidly rewound video. Darkness for two seconds, then the characters return to where they were before the dinner suggestion.

NASSER: I’m begging you … let’s not speak anymore. I don’t want to talk about anything. I’ll apologize for everything, but please, no more talking.

MOTHER: Hey! How long has it been since we’ve sat down, the two of us? As your mother, I’m entitled to tell you that I’ve missed you and that I’ve missed speaking to you. There’s only a curtain between our rooms, but I miss seeing you. I only seem to catch glimpses of you on special occasions, when you’re coming and going from the house and I’m in the kitchen. (Short silence.)

NASSER: Whatever you want, Mother. Let’s talk. (He places the table and two chairs opposite each other at the front of the balcony.) If you please, Madame … let’s talk. You people say talk is cheap, after all.

MOTHER: Who’s you people?

NASSER: Doesn’t matter. Forget it.

They sit at the table, facing each other, each one in front of his or her room.

NASSER: (He looks down, then returns to the conversation.) Okay Mother, you wanted to talk. What about?

MOTHER: (Laughing.) I miss you, you idiot. Put something on for us to listen to.

NASSER: Of course. What would you like to hear?

MOTHER: Anything. Let’s hear something to your taste.

NASSER: You got it.

NASSER goes to the laptop and puts on “Oum Nehriq Halmadine” (“Let’s Burn This Town Down”) by Mashrou’ Leila. MOTHER begins sighing audibly, annoyed at the music. NASSER quickly changes the song to Najat Al Sagheera’s “Ma Astaghnash” (“I Can’t Do without Your Love”) as if he had it queued up, knowing his mother wouldn’t like the other song.

MOTHER: This is more like it. What was that other stuff you had on?

NASSER: My taste.

MOTHER: You’re always butting your head against mine. Where you get all the energy from, I’ll never know. Enough of that, just turn it off. Let’s not listen to anything.

NASSER: Lighten up, I’m just kidding. I don’t actually hate Najat

MOTHER: As if you could! She’s bewitching, Najat. When your father was your age, he was crazy about her.

NASSER: You want to talk about my father?

MOTHER: We’re talking now, aren’t we? You don’t have to ask me what I want to talk about every few moments. Anyway, Najat sang that song for the very first time in a film called The Tears Have Dried. Your father and I saw it in the cinema.

NASSER: It’s an old film. Which cinema?

MOTHER: Well – they showed it often, not just the year it came out. Najat plays a young singer who has fallen in love for the first time in her life. She falls in love with Mahmoud Yasin, a politician. He’s a married man with children, always preoccupied, never free. She makes him fall for her, but sadly, by the end, she realizes that love just isn’t for her, nor do they grieve. She discovers that love ends, that everything ends, and that nothing can make you happy, not even love.

NASSER takes a large swig of beer.

MOTHER: Now that’s what I call acting. Just watch the scene where Mahmoud Yasin decides to finally leave her. She has a concert, and he’s listening to her on the radio and crying. He finally decides to hell with it and goes to the concert. He gets in his car and zooms off after her, crying the whole way.

NASSER: (Mockingly.) If he’s crying so much, why’d they call it The Tears Have Dried?

MOTHER: Are you being sarcastic? When your father and I went to see the film, we were captivated.

NASSER: He used to go to the cinema?

MOTHER: We only went because Najat was in the film. (Silence.) Anyway, it’s a beautiful film. You really should watch it.

NASSER: I’ve seen it.

MOTHER: Really? How?

NASSER: (Points to the laptop.) Here.

MOTHER: Such a beautiful film.

NASSER: What’s beautiful? The actual film or the one you just described to me?

MOTHER: What do you mean? Didn’t I just describe the film?

NASSER: That summary was for a film you cooked up in your head. It’s almost as bad as the real one.

MOTHER: Why don’t you enlighten me, then?

NASSER: Certainly. Dearest mother, The Tears Have Dried was directed by Egyptian director Helmi Rafla, from a script by the novelist Yousef Al Sabaai. That isn’t important, though, because they’re details and what use could you possibly have for details. You don’t care for details because the devil is in the details, and you certainly don’t care for the devil. You’re more interested in the fuzzy, velvety image of the film that you have in your memory. More specifically, you’re interested in the memory of your trip to the cinema with father. And that old hound was there just to watch Najat.

MOTHER: Watch your mouth! You should be calling him Papa, God rest his soul.

NASSER: … Papa. Now where were we? Oh yes – the film was released in 1974, which makes it very improbable that you and the Papa could have possibly seen it in theatres. Its plot revolves around a singer who falls in love with a reporter. Pay attention now, he’s a reporter, and not a politician, even though he wrote political editorials. I think you got him mixed up with papa, who was actually into politics. Anyway, as I was saying, the film tells of the ridiculous love story between Huda, the famous singer, and Sami Karam, a popular and prolific political editorialist. The whole world opposes their love, which we, the viewer, barely understand and are never given any justification for. Sami’s rivals in the elections – not political elections, mind you, but the elections for the journalist’s union – use Sami’s affair with Huda to ruin his reputation, but Miss Huda, played by Najat Al Sagheera with as much inanity as she could muster, intervenes. She sacrifices everything and sends a letter to the odious rivals informing them that there is nothing going on between her and Sami. She then decides to leave the country. The rivals then begin to mope and feel all regretful. Sami wins the election but – in the end – doesn’t make it in time to see Miss Huda before she leaves the country, knowing full well that she has given up her happiness for his. I just wanted to let you know that it’s probably the silliest movie I’ve ever seen.

MOTHER: Don’t hold it against us if we liked it.

NASSER: Us? Who’s us?

MOTHER: Me. I meant me.

NASSER: What else do you know about the film since we’re on the subject?

MOTHER: I know that I like it and that I don’t need to remember it perfectly to know it. Tell me again – when did you watch it?

NASSER: Recently – why are you asking?

MOTHER: Because I watched it before you were born. The silly plot, the frivolous direction. These things don’t matter to me.

NASSER: Oh I know – nothing new there.

MOTHER: And that doesn’t mean that you’re smarter than me or that you’re more knowledgeable. You come in high and mighty with your “Oh poor mother, you like worthless trivial things, and I’m so educated and well-read. Don’t even watch films anymore without consulting my superior analysis because I will always understand more than you ever will.”

NASSER: I didn’t mean it like that, Mother. Please don’t start moaning again.

MOTHER: I’m not moaning. You treat me like a pest that you have to tolerate. Just remember – I raised you. I tell you I miss you, and you ask me what we have to talk about, and then when we start talking, you single out everything I say and interrogate it. Just cut it out.

NASSER: Bravo, dearest mother, but you really should hold onto the reins of this conversation more tightly. Otherwise, it might start bucking and run off. I thought we decided that we weren’t going to speak anymore. We’re simply not going to agree on anything.

MOTHER: We will sit here, and we will talk. Not just about things that you want to know, but also about things that I need to know.

NASSER: I don’t think so.

MOTHER: (Sarcastically.) What a well-mannered young man! What is it with you anyway? Whenever your father is mentioned, you jump like a mouse has run between your legs.

NASSER: Quite the opposite – who would compare that fiercest of warriors to a mouse?

MOTHER: You’re mocking me again. If he were alive today, he would put you in your place. Instead, you get to bully me when I’m at my weakest.

NASSER: Please remind me – why isn’t he alive today? And you … Cut out the weak oppressed single mother act. It really doesn’t suit you. My father was committed to his politics and died because of them. Pardon me, perhaps I shouldn’t have said “died” … My father was martyred. Martyred by Abu Nidhal’s faction, the same faction he belonged to. He was shot because he didn’t agree with all of the positions they held. Abu Nidhal shot him, and that was that. The same story happened over and over again, all over the country. It’s probably happening to someone right now as we’re having this silly conversation.

MOTHER: (Goes up to NASSER and slaps him.) Watch yourself, you dog. Remember who it is you’re speaking about!

NASSER: (Silence.) Sure, sure, slap me out here on the balcony. Keep going. Slap me as much as you’d like, but remember, you’re the one that wanted to speak.

MOTHER: Yes speak, but not like this.

NASSER: Then how? I’ve forgotten. Remind me again how to speak. What did my father, who died when I was still little, leave for me other than a handful of blisters? You couldn’t afford the rent, so I picked up a broom and started sweeping the streets, fresh out of diapers. Soon after, I graduated to a shovel. I’d always come home so proudly because here I was providing for us when I was still a little boy. If you only knew how much of my body and soul I traded for that pride. Even then, according to you, I should be saving all my pride for my dead father when he’s the reason we’ve been eating all this shit.

Mother: (Embracing him.) I’m sorry.

NASSER: (Moving away from her.) What a performance! Bravo! First a slap, then an embrace. (Laughing.) My father? May God have no mercy on either of you.

Mother: I have nothing left to say. I’m going to get dinner.

NASSER: That’s the best thing you could do right now.

MOTHER goes in to the kitchen to carry dinner out while NASSER fixes his hair in the mirror. When she comes out with the food, NASSER walks with her to the balcony. Their movements are routine and natural as if they have done them hundreds of times. As they sit there to eat, the DJ booth lights up while the stage light dims. Orchestral music begins to play. The set returns to the position it was in before MOTHER got up to bring in the food. The movements of the characters give the impression that we are watching a video that is being rewound dramatically. A two second pause, then the characters return to their positions from when before MOTHER exited to fetch dinner.

NASSER: If you only knew how much of my body and soul I traded for that pride. Even then, according to you, I should be saving all my pride for my dead father when he’s the reason we’ve been eating all this shit.

MOTHER: (Embracing him.) I’m sorry.

NASSER: (Moves away from her.) What a performance! Bravo! First a slap, then an embrace. (Laughing.) My father? May God have no mercy on either of you.

MOTHER: So this is what you’ve become, you louse. You deserve all that you’re going through. I’m the one who gets to pay for your sadness, since you take it all out on me. Just look at what other people have sacrificed, you little brat. At least you’re a student in a prestigious academy. You’re going to be an actor soon.

NASSER: I don’t care about anyone else. I’m tired of sacrifice. (Short silence.) And since we’re on the topic, I’m not actually an acting student.

Mother: Then what are you doing? Aren’t you at the academy?

NASSER: Of course, Mother. Of course.

NASSER returns to the room and reclines on the bed. MOTHER follows soon after. She’s thinking of restarting the conversation.

MOTHER: Get up. I want to tell you some things about your father.

NASSER: Nope.

MOTHER: Are you serious?

NASSER: (Sits up on the bed.) Why don’t you tell me something about yourself instead? This is all so much fun, don’t you think so?

Mother: I’ve had enough of your attitude. (She goes to her room.) Damn you and whoever tries to talk to you in your sorry state.

NASSER: (Acts excited.) Great! I like this setup. Everyone in their own room.

He walks around the room, takes out a handful of mixed nuts and seeds from his pocket, and puts them on the table. He begins to eat from it and spits the empty shells all over the place. He lights a cigarette and enters his mother’s room, where MOTHER is sitting on the bed and reading a book.

NASSER: What are you hiding? You can’t hide anything from me. (She looks at him briefly and goes back to reading.) Yes, I know everything there is to know about you.

MOTHER: Oh really? Enlighten me.

NASSER: What are you reading?

MOTHER: Muzzafar Al Nawab.

NASSER: Nope, nothing wrong with you at all. You’re a veritable revolutionary.

MOTHER: Enough with the insults and rudeness. I’m your mother …

NASSER: No insults intended, Mother. I was just thinking that you … sitting just so on your tidy bed … trying to read Muzzaffar Al Nawab when you’re annoyed at me … that you aren’t simply someone reading poetry for spiritual edification.

MOTHER: For the love of God, stop putting on airs.

NASSER: Which poem are you reading? “Abdullah the Terrorist,” possibly?

MOTHER: Get out. Take your shoes off. And stop smoking in my room.

NASSER: Ah, I forgot. (He returns to his room, finishes his cigarette quickly, relishing the end of it.)

MOTHER: (She puts the book aside.) Can’t read, can’t sleep, can’t even think with you around … (She takes out the laundry and begins ironing as she continues reciting Muzzaffar to herself.) “Oh Hamad, won’t you come down and pass by like you used to. That squealing train you once took still knows us. Your secrets are safe on these paved streets. You are still my darling, you are not forgotten, but to sing in this late age will surely bring us harm.”

In his room, NASSER begins to quietly recite parts of Muzzafar Al Nawwab’s “Abdullah the Terrorist” to his reflection in the mirror. The quiet recitation turns into an emphatic performance.

NASSER: What volcanoes lay dormant in your gaze

In the corner of the room

What caravan was held up in the awful silence

Your face

What is this divinely submitting silence

A prelude to the blind, rushed, malice

Oh Abdullah the capable, oh Abdullah the truly skilled

Fix your gaze skeptically on the street

For your enemy is in the street

News of war is a litter of pups, yawning in the street

The cubed security guard catapults down the street

A people that does not know how to eat

Does not know how to fuck

In the street, does not know what’s in the street

Your knife, oh Abdullah, that inhabits the Arab wilderness

Exiled from yourself

Your mate

Your tobacco

Your wound

The sorrow of our streets

Your knife

Careful not to consign it to the kitchen

Oh Abdullah, sharpen it

Pierce it, piercingly

Do not dress a song in a black shawl during the wedding, wasting the rhythm, for we have work to do before breakfast, as grand as God

We will sabotage

If you feed the pigeons of the world from your heart, then you are a saboteur

You are bullets

You are bullets

Or you have stuffed your pockets with sweets

Oh Abdullah, you will transform into bullets

Oh Abdullah, some people are terrible sins

And some are retribution

You are retribution

MOTHER leaves the ironing as NASSER’s performance escalates. She runs to NASSER’s room, forgetting the iron on one of her shawls. When she enters the room, she is stunned by NASSER’s delivery. NASSER continues, as if he is speaking to himself.

Sorrow comes with the wind and the tap water

And the noise of the roads

Soldiers in their tanks piss on the face of my country

My face in the ground and your face in the ground

Shut up, don’t breathe

Don’t go out into the street

Do not become prey

It is forbidden to scream in your innards

Oh Abdullah, then scream

Scream, Abdullah

Spit on people’s questions

Their clothes

Their wristwatches

Their mandatory, frozen silence

Kill them with your being

Your insistence

Your love

Oh, your love makes me sigh, Abdullah, for it is sad and silent.

When he begins speaking of love, NASSER begins to cry. She tries to embrace him, but he wipes his tears quickly before she hugs him. At the same moment, they smell smoke from the iron in MOTHER’s room. NASSER runs to his mother’s room, and MOTHER runs to the kitchen. NASSER unplugs the iron and lifts it from the burning cloth while MOTHER enters with a bucket of water. She douses NASSER and iron with it. A moment of silence, and NASSER erupts into hysterical laughter.

NASSER: You didn’t want me to smoke in your room. Now the room itself has started smoking!

MOTHER: Careful, don’t step in the water.

NASSER: The water has stepped in me! Sorry if I got it dirty.

MOTHER: You still have “Abdullah the Terrorist” memorized?

NASSER: (Mockingly.) What a surprise, right? I won’t ever forget Abdullah the Terrorist … I find him to be the clearest memory of my father … Is it true you both wanted to name me Abdullah?

MOTHER: Yes. Abdullah the Terrorist was your father’s role model. We decided on Abdulnasser because your father always found fortune in the fact that nasr means victory.

NASSER: The name didn’t last long. As soon as I was in the seventh grade, I pulled one on both of you and told everyone my name was just Nasser. I hated school because it was the only place where my name had to remain Abdulnasser.

MOTHER: You’re so fixated on your name.

NASSER: (Takes off his shirt, remaining bare chested.) And what would you expect, Mother? It’s no joking matter. I can’t live my whole life with people calling me Abd – I’m no one’s slave, not even victory’s. Sometimes, I even feel inclined to bring it up to the authorities and have it legally changed. “Slave” said, “Slave” went. All the people that get to know me just call me Nasser, but as soon as the state’s involved, we’re back to “Slave.” At least you didn’t go through with naming me Abdullah. If you had, no matter how familiar someone got, it would be impossible to get them to drop the Abd and call me plain Allah. I’d be forced to be a slave, wherever I went. (Short silence.) Anyways, why are we talking about my name? Let’s stick to “Abdullah the Terrorist.” I’m surprised myself that I still have it memorized. I’m sure that I shaved some parts off, but so much of it is still burned into my mind.

MOTHER: Yes, you did shave off a lot.

NASSER: Father would reward me if I memorized parts of it even more than if I got full marks in spelling and even more than if I memorized a few verses of the Quran. Just now reciting it, I got the feeling that he didn’t make me memorize it as much as he dressed me in it, like a veil or a curse. Talking about it just now, I felt like the parts that I had forgotten were the holes from which my body was able to emerge.

MOTHER: So you can cry … That was the first time I’ve seen you cry.

NASSER: Don’t exaggerate.

MOTHER: I’m not exaggerating at all! I don’t remember the last time you cried.

NASSER: And when do you cry?

MOTHER: Ooooh, I’m always crying.

NASSER: No Mother, I mean when do you cry from your heart and soul?

MOTHER: When you’re late in coming home.

NASSER: You cry from the heart and soul when I’m late in coming home?

MOTHER: Yes, naturally. Also – when I see you upset.

NASSER: And?

MOTHER: When I remember your father. When I see this land being destroyed.

NASSER: One second Mother … I don’t think you cry when you see this land being destroyed.

MOTHER: Yes, of course I do – I love Syria very much, and I don’t want it to be destroyed, and what’s happening these days is a tragedy.

NASSER: No Mother, that’s not what I meant. I don’t want to talk politics with you. In fact, I’ve decided that we shouldn’t talk politics ever again. My question was clear: when do you cry?

MOTHER: What does it matter to you when I cry?

NASSER: It matters a lot to me – I have a right to know! I insist on knowing. You’re my mother – that you cry over me a lot is only natural: I’m your only son, and you have no one other than me, so it’s quite natural that you would cry over me. And crying for the country, that’s reassuring. Each of us does that and in his own way. But – crying when you remember my father … elaborate on that.

MOTHER: I don’t understand.

NASSER: The crying – Mother. Crying. When do you cry?

MOTHER: I cry … I cry … (She cries.) When I feel old. When the spotlight’s no longer on me. I realize how many things I’ve sacrificed and how many things I’ve let go. How many things I’ve kept bottled up. How many things were broken, but I convinced myself were fixed. And how many things I broke that I didn’t realize I had broken. Maybe time broke them, I don’t know. I cry because I didn’t know what it meant to be out of time until that knowledge had no meaning anymore. And more than anything, I cry from my heart and soul when I see you doing something bad.

NASSER: And when I do something good … you rejoice?

MOTHER: Yes, to the extent that it makes me forget all that crying.

NASSER: Well … (Silence.) Did you love anyone after father’s death?

The underlined text represents the two characters’ dialogue being read at the same time.

MOTHER: Impossible

NASSER: You’re going to say “impossible.”

MOTHER: What’s with you?

NASSER: You see that? You’re also going to tell me to shut up and stop messing around.

MOTHER: Shut up and stop messing around.

At the exact same moment: It was impossible to love someone when I was living just to raise you.

NASSER: (Laughing.) Answer me

MOTHER: (Yelling.) Great fucking God in heaven above – you’re a monster. I’ve given birth to a monster, not a human being.

She collapses on the bed, but NASSER is calm at her outburst. He lights a cigarette.

NASSER: Was that blasphemy I heard?

MOTHER: Shut your mouth, you son of a worthless dog. May God’s wrath befall you.

NASSER: Worthless dog?! Now we’re being honest.

MOTHER: I’m going to get dinner.

MOTHER goes to the kitchen to make dinner while NASSER goes into his room and turns the laptop off. When MOTHER comes out of the kitchen with the food, NASSER goes with her to the balcony. Their movements seem routine, choreographed. After they sit down to eat the food, the DJ’s corner lights up while the lights on the rest of the stage dim. Orchestral music begins to play. The scene moves backwards from there until it returns to where it was before MOTHER got up to fetch dinner. The characters’ movements make the viewer feel as if they were watching a video being rapidly rewound. Darkness for two seconds, then the characters return to where they were before the dinner suggestion.

MOTHER: Shut your mouth, you son of a worthless dog. May the Lord Almighty’s wrath befall you.

NASSER: Son of a Worthless dog?! Now we’re being honest.

Frustrated and provoked, MOTHER gets off the bed and wipes her tears childishly and quickly.

MOTHER: You want to hear it? I’ll do you one better and show you as well.

She opens a drawer from the bed and takes out a huge bag full of letters. She whacks NASSER with it. He falls.

MOTHER: Open it.

NASSER: And what’s this?

MOTHER: Open it. Not a single word. You said you wanted to know, didn’t you?

NASSER opens the bag. MOTHER takes a cigarette from the bedside drawer and lights it in anger.

NASSER: What is this rotten pulp?

MOTHER: My life. You asked me if I ever loved after your father died. Look through this bag of letters and keep your mouth shut.

She watches him as he looks through the letters.

MOTHER: Yes, this letter in your hand. Open it. (NASSER follows her orders without discussion.) Read up … read …

NASSER reads silently.

MOTHER: Out loud!

NASSER: Dear Ms. Safa, We received the news of your husband’s martyrdom with much sorrow and pride. We celebrate for him but mourn for you. We want to inform you that you have those who will support you when you are in need. You should rest assured in the fact that there are those who have committed themselves to your comfort and that of your little one, in the hope that we will be up to the responsibility of doing whatever you want whenever you need. Samih.

MOTHER: Samih was your father’s friend. He found me a job at the school about six months after he mailed this letter. You couldn’t have been older than the letter. I’d take you off my bosom and drop you off at his house. His wife would look after you while I was at work. But his services didn’t stop at babysitting. He started to drive me to the school, with the excuse that it was on his way to work. Things evolved from there until all that was left for him to do was to get on top of me. The only thing I could think of doing was to just not deal with that family anymore. The poor guy was melting all over me. His mind went light every time I got in the car with him. He started to wait for me in the street. The first time he did something, I wanted to break his teeth with my shoe. But soon, I got used to him, and our car rides began to seem like a natural part of my life. Sometimes, I’d even play along and torture him with a few words. I don’t know why I began to use my words this way. I think I was taking revenge on him for the shitty life that I was living. He kept trying to convince me that he was a man, and all I wanted was a man to make pay for all the wrath God has inflicted on me. We played this out for a whole term. Towards the end of it, I wasn’t just going to the school to do my job – I was also doing it for my car ride with Samih. If I was upset, I’d make his life miserable. When I was in a more forgiving mood, I’d listen to him flirt and pretend that I liked it, without letting him do anything other than dote on me like a puppy. Then – he stopped coming. At first I was relieved, but I began to miss him a few days later. When I realized that I was missing someone who wasn’t your father, I felt like a tramp. I couldn’t look at you. You used to a cry a lot when you were little, and in those days, I’d cry along with you. Sometimes because I was fed up of you, and other times because I didn’t know what to do for you. Sometimes, it was because I was suffocating. Just suffocating. If you want more details, you can keep looking in the bag.

NASSER: (Looks through the bag and finds letters and fragments.) “Mourning is for the crows, and you are a bed of roses. Your red lipstick is a flower that produces the most exquisite of honeys.”

MOTHER: The school principal. He asked me into his office. I went, he wasn’t there. But I found this piece of paper on the table next to a cup of coffee, as if he had left the room only seconds ago. I drank the coffee quickly and decided to take the little scrap. The words on it stayed with me.

NASSER: And so you began to wear a redder shade of lipstick and pretend as if you hadn’t found the paper. Correct?

MOTHER: Yes, but not because I was a tease or a slut. Because I began to feel that I could play this game rather than sleep with someone.

NASSER: What game?

MOTHER: The game where I would torture everyone because I felt tortured. The game where I made others feel as if their life was lacking me because I felt my life was lacking something.

NASSER: (Picks up a photograph.) A picture of you and Father. I’ve never seen this photo before.

MOTHER: Yes. This is the image I have in my mind of your father. He didn’t know how to look at the camera, and he certainly didn’t know how to look at me.

NASSER: Wow – as if he was the manliest man in the world.

MOTHER: Not to a woman. He was the strongest, most principled, most understanding man in the world – but not to a woman. He gave his whole life to the struggle. When we sat alone, he’d start talking to me about Handhala. If he wanted to flirt, he’d call me Rita. He used to love Marcel Khalife and Mahmoud Darwish’s Rita. And I used to hate her. A Jewish whore that Darwish eulogized, and Marcel popularized. Rita was on everyone’s mind those days. Or maybe just your father’s. He would say, “If only she weren’t a Jew.”

NASSER: (Continuing to leaf through the notes and photographs from the bag.) Father would have had Rita with a wink, like you probably wanted Marcel to wink at you. (NASSER takes out a picture of Marcel Khalife from the bag. He hums a tune as if he was a magician pulling a rabbit out of the hat and addresses the picture.) And what brings you here, oh Bard of the Princes? (Impersonating Marcel’s voice.) I sit in the trash heap of history. Is it not here? (He stops impersonating Marcel.) I am speechless, oh Seducer of Mothers, may you live long ever after! Did you ever tell him that you hated Rita?

MOTHER: Your father? No.

NASSER: Of course not … because …

MOTHER: Because what? Because I wasn’t mature enough to discuss things like that? Or because I had that picture of Marcel, and it’s tit for tat? (She smiles.) You’re still such an adolescent. I never told him because talking about the Gulf War would have been a better conversation. At least there was more give and take with that topic.

NASSER: (Reading.) Fuck it. I’m still younger than all your whores and my voice is stronger. May shit engulf your kindness. 2004. What is this??

MOTHER: In 2004, I decided to quit my job at the school and apply to a telecom company. I filled up an application, and they called me in for an interview. After we finished the interview, they apologized ever so nicely in their black suits and white accents. They said they wanted “youthful voices.” I couldn’t respond to the starkness of their colors, so I exited with all my grayness and poured my spite into that piece of paper. That night, I went to sleep early so I could go back to my job, which at least didn’t have a color. Not a color that could hurt or a color that could please.

NASSER: How poetic.

MOTHER: (Sighing.) Give me the bag. I don’t think it has anything else in it you’d want to know.

NASSER: I haven’t discovered anything yet. What else do you have to do? We’re still sitting.

MOTHER: I want to go make dinner. And clean up this dump. I swear to God, all you ever need to do is set foot in a place to mess it up.

NASSER: Before dinner. What’s this? (He takes a pair of pantyhose and a hair tie from the bag.)

MOTHER: Let me go start dinner.

NASSER: Oh no – you’re not going anywhere before you tell me. All those other things I could picture. But what are these?

MOTHER: It isn’t something you should know.

NASSER: Don’t worry about I shouldn’t know …

MOTHER: A pair of pantyhose and a hair tie that I’ve decided to hold on to.

NASSER: I know what they are. Why have you decided to hold on to them?

MOTHER: They’re what helped me get the job as a guidance counselor. The day after the interview at the telecom company, I felt like a doltish hag without a trace of femininity in my body. I just wanted someone to look me in the eyes and smile. After a long makeup session, I went to the school I’d been newly transferred to. The principal saw me and saw the look on my face. When he asked me what was wrong, I started crying. I think he figured it out himself. I don’t know what kind of man, when seeing a woman cry, asks her out for a night at Al Rabwa. He asked me out. That evening, I left you with the neighbors and met him at a restaurant. After we wrapped up our dinner, he invited me over to his house. He managed to remind me that I was a woman, and more. As soon as what happened … happened, he put his head on my chest and started crying. It didn’t take me long to start crying too. He said I was the best counselor in the world, and we just sat there. Not long after, I was appointed Senior Counselor at the school. He brought me the letter of appointment wedged in between the pantyhose and hair tie that I’d forgotten at his house. Now that you have this information, you have right to do whatever you want.

NASSER: (Laughing and clapping.) Why are you scared, you naughty girl? This is first time in your life that you’ve said anything truthful to me. But it’s come so late, mother of mine. What did you imagine? That I’d start crying and say something along the lines of “Mama you’ve blackened our honor … you’ve let me down.” Fuck our honor. Would you like to add anything to these confessions of yours?

MOTHER: (Runs to NASSER and embraces him.) I also slept with another man who I fell in love with. Your father hadn’t been dead for two years.

NASSER: May the registry continue to grow!

MOTHER: I’m despicable, aren’t I?

NASSER: You are the most beautiful you’ve ever been. You’re late, however … you should have told me this a long time ago. But that’s okay. Since we’re being honest, let’s keep going.

MOTHER: I’m finished. You can rummage through the bag as much as you’d like.

NASSER: I don’t want to rummage through any bags – I want you to keep talking.

MOTHER: (She sits him in her lap and plays with his hair.) I just want you to know that I am an honorable woman and that I didn’t do any of those things by choice. I would not have done any of them I could have stopped myself. I want you to fall in love.

NASSER: (Gets off her lap in anger.) Change the subject, Mother.

MOTHER: Why? I want you to succeed, and I want you to be proud of us. We did everything we could for you. It’s true, I made mistakes, but I never repeated my mistakes, and I never remarried – all for your sake … So I could raise you well. Soon, you’ll get married and bring a nice little boy just like yourself into the world.

NASSER: (Furiously.) To hell with your Lord almighty, Mother, change the subject. Go back to your confessions … to your lies.

MOTHER: There’s nothing left to confess. I’ve told you everything.

NASSER: Enough pretense. If you want to fix things, you have to speak about them first. Everything you’ve just told me is a lie and means nothing.

NASSER goes to his room, and MOTHER stays in hers.

MOTHER: What more could I tell you?

NASSER: What more could you tell me? What did you tell me? Ah, so you want me to start tearing up on the inside because my mother has admitted to fornicating on top of our family’s honorable name. Then – I’d go to my room and get depressed … Eventually, when I get over my depression, I’d come and take you into my arms and say, “Oh wonderful mother, thank you for your confidence in me, me, the enlightened young man who appreciates the fact that women also desire … that the whole affair was difficult for me to process, but here I am now and I understand.” Then you’d get up and make us some food, and we’d both sit at the dinner table like any family who has managed to put their issues behind them and can now embrace each other in love and warmth.

MOTHER: I don’t understand what you’re saying.

NASSER: And you never will.

MOTHER: Was I not right to confess to you? Or should I have been proud of the fact that I slept with two men after your father was martyred? Or should I have slept with the whole country? God’s mercy, I just can’t understand you anymore.

NASSER goes into the kitchen and takes bottle of water, a drinking glass and a large cucumber. He takes a bottle of arak from the cupboard, prepares his drink and starts drinking. MOTHER changes into her pajamas and then begins to remove her make-up.

NASSER: So Mother … would you like me to tell you what I know of your life now? How the idea of this bag, which is falseness embodied, strikes me?

MOTHER: I don’t want you to say anything, and I don’t want to say anything myself. I want to make some food. We can talk some other time. I’m tired, and I don’t understand anything anymore.

NASSER: There’s no need.

MOTHER goes to the kitchen to make dinner while NASSER remains. When she comes out with the food, NASSER does not exit with her to the balcony. This time NASSER doesn’t go to dinner, but MOTHER plays her role as usual. When the DJ rewinds the scene, NASSER stays still amidst all that. Only MOTHER interacts with the DJ. As usual, the DJ’s corner lights up while the stage dims down. Music plays. MOTHER’s movements make the viewer feel as if they were watching a video being rapidly rewound. The stage goes dark for two seconds, then she returns to her position. And NASSER begins moving again. They continue the scene.

NASSER: So Mother … would you like me to tell you what I know of your life now? How the idea of this bag, which is falseness embodied, strikes me?

MOTHER: I don’t want you to say anything, and I don’t want to say anything myself. I want to make some food. We can talk some other time. I’m tired, and I don’t understand anything anymore.

NASSER: Fuck the food. Let’s talk. The first story, the one about Samih, the friend who supposedly resembled father. The letter is fine, as far as I can tell. The ink has aged, so perhaps the date is correct. The story is believable enough. He was very nice to you. But not the way you explained it. (Mockingly.) “Things evolved from there until all that was left for him to do was to get on top of me. The only thing I could think of doing was to just not deal with that family anymore.” Enough bullshit. You were looking for a man who looked like father, and this guy was always in your face. The story evolved in your head until all you wanted was for him to get on top of you. You started with “could you please keep Nasser at your house, Mr. Samih.” And then, it was “Mr. Samih, the way to school is long and full of trouble, and little old me couldn’t possibly walk it alone.” All he saw was his martyred friend’s widow who was now his responsibility. No more, no less. The whole time, you’d perplex the poor man with innuendo that he didn’t get, at least, until he did.

MOTHER: Me?! For shame, Nasser.

NASSER: Yes, yes you! You never really wanted to sleep with him. You just wanted to fill up the gaping hole in your life. When he began to realize that there was something mysterious going on, that he could no longer understand your moods, he slowly got out of there until he disappeared.

MOTHER: But I started refusing his car rides. You’re imagining everything else.

NASSER: It should be clear to you that you didn’t know what you were doing. When you started wanting him, you thought he wanted you as well because you saw how attached he would get when you were distant and cold – just like you told me. I imagine he might have made a few hints, but you’re always gliding so high over things that you can never make them out from your altitude. It would have been easy for you to miss his hints.

MOTHER: I’d like to know why you hate me so much

NASSER: Believe me: I don’t have the energy to hate you. As for the little piece of paper with crows and flowerbeds … that’s clearly your handwriting, Mother. I know it very well.

MOTHER: (Laughing.) Yes, that’s it … and tell me, who would I write it for? Considering I’m such a free spirit, I hope it’s not to Samih’s wife …

NASSER: No … you wrote it for yourself, so you could hang it up on the wall … to archive it for posterity in this dump … and for me, as soon as I learned how to read … This paper represents what you wished the principal had said to you. Everyone used to say that black suited you, but you wanted to someone to notice your red lips and not just the black of your mourning. When the principal called you into his office, your imagination cobbled this romantic scenario together, with the cup of coffee sitting next to a love letter … as if the school was deserted and it was just you in its halls … as if the janitor transformed into a waiter. The whole story is a crock and didn’t come together as well as you’d hoped, mother of mine.

MOTHER: And that picture of your father and I. Are you going to tell me it’s not actually your father?

NASSER: You’re kidding. If I hadn’t burnt all your photographs, I’d show you how father used to look at you and look at the camera.

MOTHER: (Surprised.) You burnt our photographs?

NASSER: With no regret. My father was a man of action. It was enough for him to decide to do something for it to be done. Whenever he wanted a photograph taken, he’d look at the camera. Whenever he wanted to talk to you, he’d make you melt. Whenever he was angry with you, he would give you a slap that would make you faint. When he wanted you, he’d hit you with the same determination that he used for the slap.

MOTHER: Have some decency and shut up!

NASSER: Why this modesty all of a sudden? Are we going back to the lying? If you like lying, don’t fear – we’re sitting in the middle of half the world’s lies. He always called Rita a Jewish whore. I’ve learned the phrase from father. Everyone who knew him says that he used to always call Rita a Jewish whore and that he thought that Darwish was arrogant. They even found it odd that I liked Darwish. I’d try to explain to them that my liking for Darwish was quite ordinary, not romantic and definitely not because of the fact that I am a martyr’s son or some such bullshit. As for the fantasy you had about applying to the telecom job … this mythical job which was to restore your youth and allow you to connect with the common people, help them with all their telecommunication needs – since your kind, helpful spirit is why you became a counselor rather than a teacher anyway … All that was just a thought you had late one night, after which you realized you were thinking too much and you’d be late for work the next day, so you put the thought aside so you could make it to work on time the next morning. You were bothered by your cowardice, so you wrote that note to make yourself feel better. A counselor, huh? It’s great that our displacement helped you get such a job.

MOTHER: But I was a counselor before the move. From the Yarmouk days. It wasn’t our move to Qudsaya that allowed me to become a counselor, which is proof that all that you’re saying is bullshit and meaningless.

NASSER: Well – that’s true. I may have stretched it with that one. Perhaps I got carried away. Sure, I got carried away, but on this point alone. As for the rest, you know how much of what I’m saying is true.

MOTHER: Not at all.

NASSER: (Sighs dramatically.)

MOTHER: I don’t even know why you’re insisting that what you’re saying is any worse than what I said. You’re exonerating me of all that I’ve confessed. My accusations were always directed at myself – but pretend we never had the conversation. (Silence.) As for the pantyhose – why don’t you tell me their story as well?

NASSER: You told me that the pantyhose and hair tie were behind your appointment as head counselor, correct? Not even close, Mother – I pulled out the piece of paper that was lodged between them without you noticing.

MOTHER runs into NASSER’s room and sees him drinking arak.

MOTHER: Where is it?! Aha! I was wondering to myself where all your talk was bubbling from … Are you drunk, you lowlife?

NASSER: No mother, on the contrary – I’m quite sober. (He motions to her with the paper, which he reads.) “One day, I will forget the two of you, somewhere, when I open the door for myself.”

MOTHER: (Exasperated.) Enough bullshit. Just give me the paper…

NASSER runs around the room with the paper, reciting a few times, mocking his mother. She returns to her room, defeated.

NASSER: Would you like for us to continue with Marcel’s picture – or should I bring the whole bag and narrate your life to you, page by page?

MOTHER: Enough – for God’s sake enough. Enough of your delusions. Let me sleep at least. Sleep. Whatever you want, Nasser – I was lying to you. Good enough? Satisfied?

NASSER: I wish … You’re always lying. You breathe deceit. Would you like me to count all the lies you’ve said this evening, not counting this bag, of course? I walked through the door, and the lies began. You sit and read for me. You notice that what you’re reading is breaking my soul, but you insist on reading – even though I’d seen you from downstairs, standing on the balcony and looking down as the security forces threw the young men onto the asphalt. Is this not a lie? I take out a bottle of beer, and you make a scene about my drinking, even though you’ve cleaned my room, which contains hundreds of bottles of arak in the dresser drawers, and under the bed, and everywhere else. Then you start wailing and moaning as if you had just discovered my drinking. What is that? Is it not a lie? You know I’m not an acting student, but you try to convince yourself, in front of me even, that I’m going to become famous. More damning is when the speaker becomes unplugged and the moaning of porn echoes clearly through the room, you keep reading as if you hadn’t heard it, when, in fact, you heard it clearly. Every few minutes, you start on how we are going to eat together and do I don’t know what together … that we’re going to speak. You know well enough that all this is pretense and that what we have between us is garbage. All this is a simple summary of what has happened from the time I came home tonight, until now. Would you like me to delve deeper into the past?

MOTHER: (Screaming.) Enough! You’re sick. You’ve gone mental … You’re insane. Oh for the love of god, is there a mother who confronts her son about watching pornography? Is there a woman who doesn’t dream that her son will become a great person someday? (Silence.) I thought I was giving you your freedom, under the table. Do you think I don’t know where you spend your days and with what fucking hooligans?

NASSER: Why does it have to be under the table? Why not above it? Or above all, right in front of you? You think if you slap me, I’ll be quiet? We both know that your hand hurt you more than my cheek hurt me. Mother – I’m one of those troublemakers who want your freedom and mine. But the rottenness that has infected you makes it impossible to give you freedom. You are a human being enveloped in lies. And you’re enveloping me in fear and impotence.

NASSER sits in the corner of the bed with his back to the audience. He begins masturbating.

MOTHER: A failure. You’re a failure of a boy. You’re only clever when it comes to berating me. A real philosopher. Have you ever known love in your life? Have you ever succeeded at anything? You’re good with words and nothing else … To think that I wanted to find you a wife so you could start a family! What idiot would fall in love with you? Or would agree to live with you, you sick creature … you madman… May god have mercy on your father’s soul. At least he died without having to see you transform into this. Tell me – if I brought you the most beautiful girl in the country, right now … what could you say in front of her? What could you do? And what’s more – who is the guy you saw being taken away by the security forces who affected you so much? What punk? And what has he done? And why did you come home with your face so yellow if you’re not doing anything on my account, as you put it earlier? I fear that you’ve gone and done something stupid, Nasser … What would you do then?

NASSER ejaculates between the bed and the walls.

NASSER: You’re asking me what I would do … Are you ready to hear the answer?

MOTHER: I’d rather not hear anything. You’re just a pile of pretense.

NASSER: (Draws the curtain, opening the two rooms onto each other. He raises his semen on his hand towards his mother’s face.) This is what I would do! This is all I can do!

The DJ begins playing dubstep, and a clamor builds up on the stage. NASSER walks towards the DJ and punches him with his semen-covered hand. The DJ falls to the ground.

Act 2

NASSER stands behind the mixer. He plays with the stage’s lighting and with the music. He settles on lighting different from that of the first act. It is apparent that he is controlling his mother’s movement. He roots her feet to the ground and silences her voice as she struggles to move and scream. He goes to the corner where he ejaculated and collects the semen. He then rubs it on the closet mirror in his mother’s room.

NASSER: There. They are little people. Little people who have yet to be created, and cannot survive for more than two hours – they cannot survive for longer because they breathed in the air circulating through this dump of a house. They are your grandchildren, Mother.

NASSER looks at his mother, who is trying to scream.

NASSER: And now … I’m going to talk, and you’re going to listen. While you were talking, I was committing a massacre. Do you know how many little people there are here? About half a billion. They died because they were created. I created them, and I killed them. Mother, you need to understand clearly that I am criminal. Or, you know what? I am a god. I am both at once, a criminal and a god, destroying as I create. I use purgatory well. It is a place of neither life nor death, and I use it well. I have practice, you see. I always do this. Just ask the television. The little people were still inside of me until the television started whoring itself out at me. (Silence.) All I wanted was to do something. To accomplish something. And the result? Am I a murderer? A victim? A moron? I don’t know anymore, Mother, I don’t know. All I know is that about half a billion died by my hand in less than two minutes. Believe me, the world is ultimately like His ass. (Silence.) Even though it doesn’t always resemble it. We sometimes talk about how a certain number of people died – and now countries don’t war on each other anymore. Or that life in a certain place is really much better because a certain number of people died. Rest assured, however, that my certain number hasn’t changed a thing, nor will it. Half a billion is like your worn out shoe. I daresay that one of those half a billion could have been your grandson. What are you thinking now, Mother? Are you thinking that all this is so shameful? Are you wondering how I could do such a thing in front of you? Think about what’s stuck to the mirror in your room, Mother. Contemplate yourself and your life. (Silence.) Today, on the television, they were showing a massacre. It was very unlike this one. Just like that, they showed it, and the world went mad. The reporter made herself out to be so affected by the story. All I could hear was her snapping away at her chewing gum. I’m telling you, she was chewing gum while they showed the massacre. I don’t know if I imagined her chewing the gum. (He looks over at his mother, who has given up moving and screaming.) Oh, I forgot. But promise not to scream. (She nods. NASSER goes to the mixer, turns on her voice, and un-paralyzes her. She runs to the bucket of water and drinks what is left in it.)

MOTHER: You want to kill me, you animal … You would hate it if I died naturally … as if I didn’t already have one foot in the grave … Why are you doing this?!

NASSER: (Pointing to the mixer.) Another word and I’ll paralyze you.

MOTHER: (Sits on her bed, still and growling.) May you fail at everything you ever attempt.

NASSER: It wasn’t just the sound of the gum. I was also confused by the red of her lips. It mixed with the red on the ground, into every red I’ve ever seen or read about in my life. The camera shifted to focus on arms and legs, unrecognizable limbs … as if the chopped-up people were a jigsaw puzzle and the reporter and all the analysts and pundits didn’t know how to assemble the pieces into a whole picture. I couldn’t make out what they were saying. Suddenly, someone who understood the puzzle walked onto the frame. A mother, carrying her dead son’s hand, looking for the other pieces of him. Her clothes were dusty and torn. At this point, I couldn’t make out what I was watching anymore. The woman’s tits, the son’s hand, the luxurious studio … I was disturbed, Mother, and felt I had to do something. (Silence.) I couldn’t do anything other than this. I quickly grabbed hold of the remote with both hands because I knew where my hands were going. Nothing like the boy’s hand, which went flying off of his body towards his mother. I grabbed the remote like those people you see holding on to a life raft with a rope, being dragged through the ocean. I lost track of myself until I was already in the middle of my massacre.

MOTHER: Oh God! I want to die.

NASSER: (Reciting sarcastically.) “In Al Quds, contradiction and wonder are at ease. Worshippers do not deny them like pieces of cloth, flipping through the old of them and the new. There, hands touch the miracles. In Al Quds, if you shook hands with an old man or touched a building, you, oh Son of Nobles, would find a poem engraved on your palm.” Oh how shitty this part is. Perhaps I should like a poem engraved on my palms so I wouldn’t play with my cock. Or perhaps the hand that the mother was carrying should have had a poem engraved on it, so it wouldn’t be ripped from the body of her son. Enough bullshit. That bought-off poet should have paid attention to the men that came before him, the ones who taught us to close our hands, to not beg for money or food. Those men busied our hands with two things: the rifle and the victory sign. (Makes the victory sign with his hand.) See how perfect it is? It closes the hand off completely, and it even leaves two fingers open in case you would like to gouge your eyes out and stop seeing.

MOTHER: (Yelling.) By God, I hope to go blind so I never have to lay eyes on you again.

NASSER: What do I want with all this clamor. (He turns his off his mother’s voice and paralyzes her with the mixer.) Now you can scream as much as you want. Scream, Mother, you should be screaming! Now where were we? Oh yes! The morning massacre, at the point where the wailing mother aroused me. Wailing much like you, but she had a voice at least. I’m not sure how her wails and screams rearranged themselves in my mind, becoming soft whispers. Her cries for her son signified to me that she was screaming for me. After I did my deed, I felt that maybe I was jealous of the man that committed the atrocity on the television screen, and I wanted to prove that I was faster than he was. I knew how to commit a greater massacre than he did, and I knew how to do it in complete silence! Nobody else did. Not the war criminals committing massacres on the television, nor the romantic poets, so taken with the romance of war … (Laughs.) The romance of war … Is there anything more trivial than the language we invent? The romance of war … I see that you’re relaxed … You look so stoic … Since you’re relaxed, I’ll tell you a tale.

NASSER brings the couch from his room and places it in front of his mother. He wears a robe from his mother’s closet and puts some make up on his face, quickly and comically. He stands on the couch and begins speaking as if he were a hakawati (a traditional Arab storyteller). We hear MOTHER try to speak every once in a while, but she stops and reclines when she realizes she has no voice.

NASSER: Once upon a time, there was a gigantic man, yes, gigantic, a man, as manly as a bull, virile, a magnificent warrior, and he was known by a girl’s name, Abu Layla they called him. This man swore, for reasons I forget … oh I remember now. His love for his brother. He swore after he fell in love with his brother … his brother died, killed naturally, as all men were killed during those times … it doesn’t really matter to me, but all the stories we love tell us that we all died violently back then … Abu Layla’s brother died, killed by his cousin, so Abu Layla decided to cut off his cousin’s line of descent, which was naturally his own line of descent … No, no no, the hakawati would never tell us the story like this; quite the opposite, he’d try to excite us with it, like a whore … but let’s just agree that I won’t provide the excitement for you, quite simply, I don’t know how to. You will provide the excitement using your imagination, especially considering you’re so adept in the realm of imagination already. You can continue to rely on your imagination because there are no hakawatis left, that’s it for them, and they’re all gone. Residing in the trash heap of history. Even if there were a hakawati left, you couldn’t see him as his sermons are all directed at men, unlike you, who offer your sermons to everyone. Men, women, young and old, anyone you wanted, really, you could sit down and slap with a sermon. Just like the men of religion, you can sermonize at anyone anywhere … This one comes on the radio, the television, the pulpit, he’d pop his head out of your asshole and drop sermons everywhere. He’d pop his head out of your ass when he had completely settled in there after you got married. Before the marriage, he was living up front, reclining on your hymen until it was ripped out by my father, who I think ripped open your asshole before he made you bleed on your wedding night. He made sure to only enter where a sheikh wasn’t present.

You can’t speak, so I’m going to sermonize the rest of the story. Abu Layla loved his brother to the point of madness, no, more, to the point of deranged lust, yes that’s more like it, and Abu Layla lusted … (Corrects himself.) was so attached to his brother that he became the killer of his cousin’s lineage, which was also his own, so he spent forty years killing the lineage until he himself perished and died. What an imbecile you are, Abu Layla! Do you want to exterminate your lineage? Come, I will give you a lesson on how to kill half a billion of your line in under five minutes, half a billion, but there was no science to explain to you that what you could accomplish in under five minutes is half a billion; there was no relationship between you and the television screen, for there were no televisions in your time. I have these resources. This is not to mention that you had a number of women in whom you could deposit your seed as you are the master of seduction. You did not use your hand, not even once, I presume. You are the master of seduction who did not realize that the relationship between his hand and his member would quench his desire for death, would earn him forty years of idleness. A number like half a billion would sate the urge to kill even in you, Abu Layla. I’m not a master of anything, and this is what made me kill faster than you ever did. I am a man addicted to the television. What would the hakawati say about me? Perhaps he fell asleep in his trash heap because he did not know what to say about me, could not find a way to excite his listeners who came to hear of a massacre that occurred in less than five minutes. The hakawati fell asleep in his trash heap because he was forced to tell a tale faster than it took to complete. I don’t know what forced him to do that, but he began to wonder where he could extract excitement when he only had a minute or two at most. Or perhaps the crimes he spoke of were dwarfed in his eyes before the magnitude of my crime. (Screaming.) “But he saw you as so small, oh Salem, he saw you as so small and stupid.” (He cries.)

Silence.

He goes to the mixer and allows his mother to speak.

MOTHER: (Screaming.) I want to die!

NASSER silences his mother again and presses a button on the mixer. The scene rewinds at an unbelievable speed. As the scene is rewound, he goes back to being a hakawati. The rewinding stops at the point where NASSER goes to wipe his semen onto the cupboard. NASSER repeats the action, and the scene begins anew.

NASSER: There’s something I want to say. I want to inform you that I’ve decided to put on a play. All I wanted was to do something. To accomplish something. I couldn’t accomplish anything other than this massacre. I told myself I had to write a play, because writing for the theatre cleanses the soul. But I didn’t know where my soul’s filth would end up, or on whose head it would be strained. I started writing, and the more I wrote, the more words I would end up with. The words began to birth each other, to propagate. The pen would engorge, and the pages would contract. I wrote and wrote and wrote, but I soon discovered that only some of what I was writing made it to the page. The rest remained on the table where I was doing my writing. I tried to fix the text and collect myself from off the table. I found that I had written a text that was more dense with thought than I could have imagined, or even understood. When I tried to understand what I had written, neither reading nor analysis helped me comprehend. Instead, I tried to imagine a production of the play. I tried to read what I was seeing in my mind, but it was futile. I didn’t understand anything. I drowned in the details of the production. I began to replace the actors, switch the director … But I found myself stopping at a point in the play where a character was speaking. In my mind, I saw the actress playing the character wearing a short dress. Very short. I was entranced by the dress. I waited for her to move so I could get a peek at what was under the dress. This was all I could see of my production, Mother. All at once, I found myself fucking the actress as she was trying to play her part. I shoved my cock into her mouth as she was speaking her lines about work. I came on her forehead, and she held it up, proudly. When this happened, I noticed my massacre and realized my entire play was sitting in a corner of my head, and in the other corner, millions of other thoughts and things were at work. I did not understand them, and I did not understand my play, and everything was blending together, forcing me to commit this massacre. I didn’t know that the corners of the head could fall into each other like that. But the play … the play is the most honest play you’ve seen in your life. You didn’t have to know that all the corners of the head were crashing into each other at that moment, Mother … It could be great, Mother, because in that moment, you would be creating … or murdering.

He presses a button on the mixer and allows his mother to speak.

MOTHER: That’s enough … for God’s sake… I’m going to die, Nasser.

He turns off her voice again.

NASSER: No, it’s not enough. We’re still at the start of our story – don’t you want to see my play? Anyway, you couldn’t do anything if I let you speak or move. Damascus is dead, and there is no one to help you.

NASSER runs to his table and takes out a few papers. He rearranges the room into a makeshift theatre by pulling the bed from his room to the middle of the stage, using it as a makeshift stage. He takes four items of clothing out of his mother’s closet and begins to draw on them using his mother’s makeup. These pieces of clothing represent the actors in his play. He uses the objects while he reads from his play, producing it as a puppet show or a theatre of objects where he uses the objects to clarify the difference between the characters and the actors he is speaking about. It is important that NASSER arrange the house in such a way as to make it look derelict and destroyed.

NASSER: The title of the text is lifted from the introduction to the Dictionary of Drama. Some words Saadallah Wannous said: “Of course, it would not have been possible for those parasites who could neither write nor critique to expand and fill blank pages with trivialities and superficial analyses had we had cultural traditions that were revered by all.” It’s a little long for a title, but it’s good, and I want the whole thing to be the title.

The characters:

Her, played by Abla

Her Husband, played by Jamal

Her Lover, played by Kamal

Her Beloved, played by Nidhal

Author’s Note: If any director would like to present this text, then it is permitted for them to do so. The only requirement is that they understand it. Secondly, the play is a single unit, and there is no play within the play within this text!

Scene: Her and Her Husband stand on the stage

NASSER tosses the papers into the air and begins speaking the play from memory. Sometimes, it seems as if he is improvising, and during the performance, he goes to his mother and makes her clap. She claps slowly, bemused by the hysteria that appears to have overtaken NASSER. She seems to be able to move her hands even when NASSER fixes them in place and even though he’s silenced her with the mixer.

Her: Where are you going?

Her Husband: To work

Her: What work?

Her Husband: The work I always do

Her: (Feels insulted.) Why don’t you answer me like I’m a human being?

Her Husband: And what did I say, I said the work I always do.

Abla: (Feels sorrow. (On the inside.)) You don’t understand me.

Jamal: (Feels anger for Abla’s feeling of sorrow.)

Her Husband: (Vents Jamal’s anger, mockingly.) You are deeper than I can handle.

Her: I’m sorry. I didn’t mean it that way.

Her Husband: That’s your style. You cause problems then act like an angel. (One of the audience members in the theatre would like to be in “His” the character’s place to slap her. Another audience member sitting in the corner feels anger, not because of the audience member who would like to slap Her, for she (the spectator) did not see him in the darkness. She’s angry because of the moving scene.

Her Husband: (Is swallowed by the earth.)

Her: (The actor Kamal passes in front of Her. One of the audience members: Bravo Kamal. She treats him as if he were her beloved.) If you please …

Kamal: What do you want?

Her: I’m a girl with a lot of connections and who excels at everything. I even excel at being superficial sometimes and ignorant at others. I am beautiful, and you are not ugly at all.

Abla: (On the inside.) I am a girl that wants to have sex with you without speaking about anything at all. I hate myself for wanting this, but I know that with you I cannot repress my urges.

The Beloved: (Knows what she holds inside her even if she hasn’t acted on it.) I love a certain girl.

Her: (Knows that she isn’t the one he means.)

Abla: (Tries to convince Her that, in fact, she is the one he means (saying this on the inside).) Thank you, it is an honor, it is an honor I did not dream of.

Her: (Is convinced of Abla’s words and so does not answer.)

(Half the audience leaves the theatre. The director laughs and then suddenly begins to look dazed. The rest of the audience are engaged in the tale and look as if they have not understood anything up to this point.)

The Beloved: Farewell.

Kamal: (On the inside.) What a whore!

The actors disappear, and Nidhal takes center stage.

The Lover: (Runs around the stage like he’s obsessed, looks to the clock, then continues running. He tries to convince himself that he is nonchalant. She appears and greets him from afar.)

Nidhal: (Is rupturing.)

The Lover: (Is smiling.)

Her: Shall I tell you a secret? I am in love.

The Lover: Don’t tell me (Silence.) Who is he?

Nidhal: (On the inside.) The bastard.

Abla: (Is pitying him.)

Her: The beloved.

The Lover: Do not love anyone, not even myself, I beg of you, and do not hate anyone, not even myself, I beg of you. (Feels guilt over all that he has said to her.)

Nidhal: (Is crying.)

Abla: (Is crying in pity over him.)

Kamal: (Is laughing.)

Her Husband: (Takes Her by the hand and leaves.)

Jamal: (Wishes he were dead.) What did I do wrong? (On the inside and with malice.) I will lock you away from the world, one of these days.