An Interview conducted by Fawzia Afzal-Khan, with Shahid Mahmood Nadeem and Sohail Warraich of Ajoka Theatre, March 28th 2018. By Fawzia Afzal Khan Arab Stages, Volume 8 (Spring, 2018) ©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications

The interview was conducted on the premises of the Ajoka theatre group’s office in Lahore, Pakistan. Click here for another inteview conducted by Dr. Afzal Khan for BBC.

Madeeha Gauhar

Fawzia Afzal Khan (FAK): I’m talking with Shahid Mahmood Nadeem, playwright and of late, the director of Ajoka in Lahore, and Sohail Warraich, a long time Ajoka member in various guises and capacities. Hello Shahid and Sohail–I have a few questions that both of you can answer as you deem appropriate, and we can see how it goes:

First of all, please tell me when you did you two join Ajoka? It was founded by Madeeha Gauhar in 1983, so she is the founding director, and then Shahid came on board later; first as a playwright commissioned to write a play (Barri, translated as Acquittal, in 1987), then as full-time in-house playwright and more recently, as director. Sohail has his own history with the troupe. Tell me about those early years, events, reminiscences that pop out of your memory. What was it that made you two join Ajoka? What was it like then, and what would you say it has become now?

Sohail Warriach (SW): Well, actually, a theatre group named Ajoka was founded much before Madeeha put her stamp on it, which was founded by Shahid and others, when Shahid was a student in Punjab University…I think it was in 1969 or 1970?

Shahid Mahmood Nadeem (SMN): 1970.

FAK: Did you mount any plays under the banner of that earlier Ajoka? Tell me a little bit about its genesis…

SMN: Many of us student and cultural activists got together in 1971, which was a very depressing time after the fall of East Pakistan, as we shared a desire to build a new Pakistan, not just to be defined by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto[1] though he was our hero–but by other committed workers in the PPP (Pakistan Peoples Party), to carry on as a nation. It was in these circumstances that we decided to form a political theatre group. Aitzaz Ahsan was one of the members, Usman Peerzada was there, Salman Shahid was there.[2] We got together.

FAK: All men?

SMN: All men. Aitzaz Ahsan even began preparing a constitution for our group, but of course as we know, the group didn’t succeed in establishing itself. The moral of the story is that if you begin with a constitution for a theatre group, it is not going to take off! Anyway, we did start off by rehearsing a play. It was a play about the fall of Dhaka, which was being rehearsed in the Civil Services Academy in Lahore. That was because my fried Shehryar Rashid who later became an ambassador, was training there at the time. We were actually rehearsing in his room. It was quite a bold and challenging play.

FAK: Whose play was it? Tell me a little bit about it…

SMN: I was developing it. It was a play about Pakistani POWs who were in an Indian prisoners’ camp, who were now living through and haunted by what they had done, what had happened during the War of Bangladeshi Independence. The word went out and the people came to know that the rehearsal was going on. After a few days, Shehryar was asked by whoever was the boss at the academy at that time, that if he wanted a career in the diplomatic service, then his involvement in this play had to cease. So, the play fell through.

FAK: What year was that?

SMN: 1971, it was right after the fall of Dhaka.

FAK: Had you known about this play Sohail?

SW: I have heard only that a group called Ajoka was formed. What Shahid has just narrated, we used to laugh when we learned that Aitzaz Ahsan was involved and that he was writing its constitution. We were amused because as we all know, he later went on to become one of Pakistan’s most venerable constitutional lawyers.

SMN: One interesting thing about this history is that the word Ajoka was coined by me.

FAK: Interesting indeed…

SMN: I still have that paper on which I wrote out different names for the group we were trying to form…

FAK: Like Ajj Da? [trans: Of Today)

SMN: Yes, it is a colloquial Punjabi word, Ajoka. People started talking about it in the early 70s; so the word was in the air, and Madeeha must have heard the name.

FAK: I see.

SMN: In 1984 when she decided to form the group, this name was already there and she knew that it was an initiative of some progressive people. So in a nutshell, you can say that I conceived Ajoka and Madeeha delivered it!

FAK: (laughs) That’s a good one. OK. Does she agree with this reading of yours? Would she dispute it?

SMN: She can’t dispute it. She knew that this name existed but she didn’t know about my role in it.

FAK: Alright, it seems very fortuitous. Which leads me to the next question—we will get back to Sohail about his involvement in a bit– my next question for you, Shahid, is what was it like for you, when you came into this second incarnation of Ajoka first as a playwright and then you married Madeeha and shared the public platform with her as its founding director, and in the private sphere, a domestic life. Tell us what have been the highs and the lows? Share some intimate memories, something people would really appreciate learning which they don’t know perhaps, something from your heart…

SMN: Yes, well…the first time I heard about Ajoka theatre was in a news article in the Herald I think.

FAK: And this is when you were in London, in self-exile, right?

SMN: Yes, I was in London and it was reported that a play had been staged by Ajoka theatre under Madeeha Gauhar’s direction. I had known about Madeeha previously because she was a well-known actress, a young actress. At that time I had been working for Pakistan Television and she was a PTV actress. But we’d somehow never met though we did know of each other. Perhaps because at that time I was not doing drama. I was doing some documentaries and cultural programs and was involved in trade union activism. So my line of work was a bit different and our paths didn’t cross. But I was impressed by this Herald article and then when…

FAK: Which play that would be?

SMN: It was Jaloos. It was like the mid-80s. Then when she came over to London on a scholarship and I finally met her, that’s when she said she had seen one of my plays, my first- ever play written when I was a student, which was performed at the famous Kinnaird College for Women, as part of the Najmuddin Drama Festival[3]. The play was called Mara Howa Kutta (trans: Dead Dog). So this was the first play I wrote as a university student. I had a short story with this title and my friend Shehryar said why don’t you convert it into a play, it has all the potential. I replied, “anything to gain access to Kinnaird College!” (laughs). So I wrote this play and it did very well. It was given the award for best play that year.

FAK: It was in written in Urdu and performed in Urdu, right?

SMN: It was in both Urdu and Punjabi.

FAK: That was what year?

SMN: It was in 1971 or maybe 1970…

SW: It was before the fall of Dhaka…

SMN: Yes, General Attiq-ur-Rehman was then the Governor of Punjab. So the two best plays were performed at WAPDA House auditorium, the premier auditorium at that time, in the basement of the WAPDA House. The Governor was the chief guest. The play ends a city neighborhood where residents find a dead dog in the middle of the street and the whole play is about what they (don’t) do about this “problem,” they try to ignore the sight and smell of the dog and carry on with their business. And then they try to find all kinds of interpretations for the dog’s presence there, spiritual and political and whatever. Only there is a madman- a device which became a regular feature in my subsequent plays–who keeps on pointing towards the dog. You can say that this madman might be me because I’ve kept on reverting to this character for over four decades now! Anyway- at night, the dog disappears but its stench remains. The residents cannot sleep, so they come out of their houses, all the characters, and they ask each other where the stench is coming (bo kithon aa rayee ai) and then they start accusing each other. Finally, the madman starts laughing, and points to everyone on stage….

FAK: That the stench is coming from all of you…

SMN: Yes, but at the WAPDA event, to “honor” the then-Governor Punjab, General Attiq, I quietly advised the actor playing the madman to jump down from the stage and point towards people sitting in the front row including the good General! He did that and it created a great sensation! So Madeeha had seen that play when she was still a student in High school. She joined Kinnaird College a year later. So where were you in 1970?

FAK: I would have been an 8th or 9th grader at the Convent of Jesus and Mary (which Madeeha also attended)-as I was 2/3 years her junior.

SMN: yes…Madeeha too was not a student of Kinnaird yet, but she had come to see the play. She remembered that play and that it had had an impact on her. So when she met me in London many years later, she asked, “you were the one who wrote that play?” I said “yes.” “So what happened, you haven’t written more plays”, she asked. I said I had written more plays but a play was useless until and unless it was performed, which hadn’t happened because there were no theatre groups in Pakistan anymore. She said: “Well, you’re wrong; we have formed a theatre group and we are looking for good scripts.” So that’s when she took the script of Mara Hoowa Kutta for Ajoka to perform, and asked me to also write a play for 8th of March—International Women’s Day, 1987– which I did; no one could refuse Madeeha! You should remember that play because you played a major role in it. Also, you were the one who brought the first video recording of that play (Barri; trans: Acquittal) to me in London. It was for the first time that I saw how a play of mine was done by Ajoka. I liked what I saw–so that was how I got involved in Ajoka.

FAK: The rest is history, as they say, and of course I remember fondly my role as Maryam, the “mad” Sufi singer of that play, which turned out to be so productive in different ways for my own professional life. So tell me, what has it been like getting involved in the day-to-day running of things in Ajoka over these past 3 decades? Also sharing, in a way, with Madeeha, both the excitement –and the challenges surely –of being two strong people with very particular ideas about how to do theatre? From the outside it looks like a very successful teaming-up, but what were the things that you two quarreled about in terms of theatrical and political issues that inform your visions… Do you see eye to eye on everything?

SMN: I think the essentials of theatre, the role of theatre and let’s say the goal of Ajoka, we shared that, which was to promote theatre as a platform for political discussion, awareness about human rights, social awareness etc. So Madeeha’s main concern, or I would say the preference, would be to do good plays, aesthetically good plays with a lot of costumes, music and culture although with strong message and my challenge was how to create a script which is socially meaningful as well as artistically beautiful and enjoyable which audiences from all classes can join in and appreciate. That’s how it started. Madeeha was– is– a very strong willed domineering director. You can’t interfere too much with direction. So although as a scriptwriter available all the time, I could have played a more active co-director role, that did not happen until just lately after she became ill. Mostly we would discuss the play before it was written and once it was written it was her baby and she would nurture it. At least initially I didn’t interfere too much. So that’s how it developed. One thing which although as a political activist I would have been more concerned about but it was Madeeha who insisted that we should use as much Punjabi as possible. Write in Punjabi, she told me. Because as a director she realized that when actors, because our actors came from different social classes mostly Punjabi speaking background and she realized that when they start speaking in Urdu, (it brings) a lot of pressure on them and they are not trained actors. The moment you let them speak in Punjabi, they suddenly feel empowered and they open up. And secondly, she believed that in terms of communication Punjabi would be a better language. And that was something that she introduced. My uppermost concern was to give political and social content which is relevant and which is also enjoyable. This is like walking on a very tight rope. On the one side you have entertainment which can become banal and on the other you have content which can become propaganda and dogmatic. So I have been walking this tightrope and Madeeha has been decorating that tightrope.

FAK: Interesting! We are going to come back to that question with your latest production but I want to ask Sohail who has been with Ajoka from pretty much day one. So you can talk a little bit about your role in Ajoka, how has it changed through the decades and what attracted you to Ajoka, how did you get involved with it in the first place…

SW: Fawzia, 11, 12, 13 May 1984 were the dates when Ajoka did its first play Jaloos (trans: Protest March, written by Indian playwright and theatre director Badal Sircar[4]). These were the dates when I was visiting Lahore for my admission to the University of Engineering and Technology. I came here for the submission of application forms etc.

FAK: And you came from Sargodha?

SW: Sargodha, that’s right. I did my intermediate from Cadet College Hasan Abdal and was visiting Lahore. I used to stay with friends. I learned that a play was being staged in a house. But I didn’t know what the play was. Later I read a review in a newspaper. Coincidently in those days, there was a long teleplay in which Madeeha was acting. Nisar Hussain used to produce those long plays.

FAK: What was that play?

SW: If I can correctly recall, it was about a Bureaucrat’s life and his wife, I don’t know exactly the name. I only know that Salman Shahid was playing the other role. You can read between the lines and there were some political lines and with that oppressive situation. It was between the line and there was political content in the life of a bureaucrat and all that, imagine it was Zia’s era. That I watched. A few days later.

FAK: You liked that performance.

SW: So three things happened: I learned that a play has been staged in Lahore, I saw Madeeha in the long TV play and then I saw Madeeha’s interview in TV Times done by Adil Najam. In that article I learned that she is not only an actress but a political person. There were a few lines in that article about Jaloos and the way she described Ajoka that really appealed to me

FAK: So interesting…Was it the same Adil Najam who is a Professor in Boston and at one time served as Vice Chancellor of Lahore University of Management Sciences?

SW: Yes, the same. Those lines from his interview of Madeeha attracted me because they showed me that she had a politically radical mind. Then, while at the university I learned that half of the Jaloos cast of the Ajoka team was from the University of Engineering and Technology. That’s how I connected…

FAK: That in a way is very strange…about so many actors being Engineering students…no?

SW: We were the highest number, then came students of Government College and the third was NCA (National College of Arts) in that first grouping, and one actor was from King Edward’s Medical college. The same guys I used to hang out with…

FAK: Mostly it was men?

SW: Yes it was mostly men. From UET, Qamarunnisa, she was doing electrical engineering, she was also there. Then I used to hang out with the same guys in the university politics, so I learned about where Ajoka stood, politically speaking. Then I requested Adnan Qadir, who was from the UET and is currently a civil servant on long leave. I said Adnan, you know, they were rehearsing Chaulk Chakkar (an Urdu-language adaptation of The Caucasian Chalk Circle by Bertolt Brecht). This was Ajoka’s third play, third production in September ‘85, so I requested my friend that I wanted to join Ajoka and I told him that I used to be a debator and very active in student politics against right-wing political ideologies. There used to be a lot of violence on campuses, and we were fired upon directly by the Jamaatis (student wing of the right-wing religious political party, the Jamaat-i-Islami) several times. I have seen the violence when it was its peak at the campus. And the Jamaatis used to have two MNAs (Members of the National Assembly)-Hafiz Salman Butt and Liaquat Baloch, they brought Kalashnikovs to the university, you could see them handing over guns to Jamaati students. So we were really in the hotbed of political clashes in the university. The unions too were banned on the campuses.

FAK: That was when Shahid left?

SW: Shahid had left in 70s, he had left for England, and was in exile, because of his involvement in student politics, which had made him dangerous in the eyes of the Establishment…

SMN: if you see the first cast of Jaloos, the list of names and see as to where they are now, it will be very interesting.

FAK: Oh yes, tell me…

SW: Well, there is Rana Fawad, who claims that he brought me into Ajoka…

SMN: Rana Fawad is now the owner of Lahore Qalandar team of the Cricket Super League.

FAK: OMG, what a celebrity and a wealthy one. Does he support Ajoka?

SW: Yes, he came to see one of our plays a year ago. He came up to the stage of the performance and said: “my beginning, my start, my political consciousness was all with Ajoka.” He gave a long speech.

SMN: But no donation!

FAK: What a shame…

SW: Dr. Farhan, a wealthy doctor now in the United States is another of our early cast members and supporters. He makes it a point to take all of us at Ajoka out to a nice dinner whenever he visits Lahore.

SW: And Rashid Rehman has been an Ajokan too…

FAK: Rashid Rehman? You’re kidding…I had no idea he could act!

SW: He was the old man in Jaloos, back in 1987. He was a big-time leftist as you know, even had to go underground for supporting the Baluch nationalists at one point, and was, until recently, the editor of the English-language newspaper, The Daily Times.

SMN: Then there was Hamid Mir…

SW: Yes, he was also in Jaloos in 1987…

FAK: Who later became a well-known TV anchor, right?

SW: The current biggie journalist. Yes.

FAK: Wasn’t he also fired upon by the Agencies?

SW: Yes, he was. Anyway, these things attracted me and I told Adnan and others of my progressive college friends that Ajoka is a tool of political expression and I want to be part of their mission. Madeeha did ask me two or three questions and then said, OK.

FAK: You are in?

SW: You are in.

FAK: So you became an actor first?

SW: So I played up to seven roles, I can’t even remember: farmer, trader, servant, sepoy, petition writer etc. I kept changing roles on stage, and even in my life—very Brechtian! Coincidently there was one scene where there was suspense and we were performing on the terrace of the Goethe Institute. Chaak Chakkar was the name of the play (an adaptation of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle). We made a river by the edge of the terrace using old sarees. Faryal was the lead actor. We had massive press coverage, and a big photograph of our production appeared in The Star newspaper. We got a lot of encouragement, and massive press coverage. Those were the days when Zeno (Safdar Mir), Sibt-e-Hassan, Hussain Naqi, Ahmad Bashir, I. A. Rehman, you name them, all well-known progressive writers and human rights crusaders, they used to come, sit and watch our plays, write about us. The Star used to give us the maximum coverage. And Viewpoint also, edited by the legendary Mazhar Ali Khan.

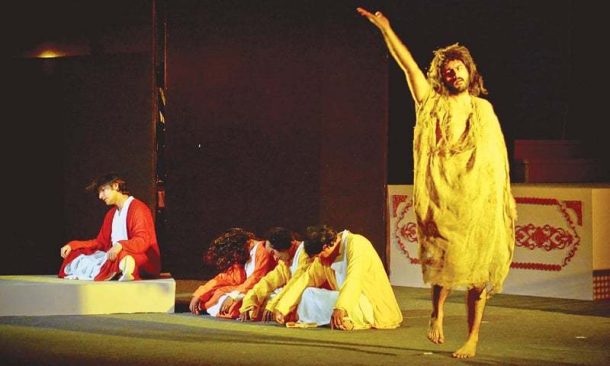

Ajoka Production of Chaak Chakkar.

SMN: Father of the famous UK-based socialist leader and author, Tariq Ali.

FAK: The Star has faded now?

SMN: It used to be a major publication of the Dawn group; it gave a lot of coverage to culture and the arts.

SW: On Tuesdays we used to get it, inserted inside Dawn newspaper. And then I learned that Madeeha is leaving for one year of studies as she got a scholarship to the UK. That was when the first partition, or you can say the first division of Ajoka happened. But it was friendly.

FAK: So what do you mean by division?

SW: Division in a sense that our certain friends who later formed Lok Rehas, they started to talk to us that they wanted to switch over to Punjabi language and idiom entirely, and they wanted to form their own Marxist theatre group. We all knew that half of the team would not be the same.

FAK: And was Mohammad Waseem among them?

SW: Mohammad Waseem, Nisar Mohiuddin, then Qamarunnisa, Aashi was there…

FAK: Was Huma Safdar among them too?

SW: Huma was but she did later do Punjwan Chiragh with us…

FAK: So they were all part of Ajoka first…

SW: It was mutually agreed that fine you wanted to do all plays in Punjabi, a particular brand of Punjabi, fine, you wanted to do that style. Fine you do it; it was decided that we would do this one play together. We had a party at aunty Khadija’s [5] annex, as Madeeha used to live there. We parted in good manner, amicably, and it was decided that there would be no bad feeling towards each other. We used to come in each other’s plays, used to lend props and costume whenever anybody needed them.

FAK: Was there a political reason behind the division? Like what they wanted to be, or they thought they were more radical…

SW: To tell you the truth all my friends went into Lok Rehas, my politically radical friends. That was their reason. I would say, Ajoka’s first three productions, in which many of them were involved, was for most of them training if not the apprenticeship. They did some of their first theatrical work and then departed.

FAK: That’s coming back to me from my old research[6]…

SW: When Madeeha was about to leave for abroad in 1985, I came to see her to say goodbye and did a short interview with her for my magazine, a campus magazine called Youth. However, it was banned on all campuses and we were told that there was going to be no extra-curricular activity. So some of us collected money and brought out a journal of our called Orion, it has got some Greek meanings that were relevant for us—it burns the brightest of all constellations when the night is dark. So I came to her to do a short interview for our newly-minted journal. Madeeha said to me that she was about to leave for a year, but you in my absence, had better not leave Ajoka! At that time I was a young guy, she you know appreciated my work, said to me that you are involved in progressive politics also, and you are an organized person as well. So Ajoka should continue and you people are allowed to do whatever you can to keep it alive and do rehearsals and meetings. So those words of Madeeha remain in my mind that even in her absence the mission of her theatre shouldn’t be abandoned. So we continued. Madeeha was abroad, so we did whatever was possible for us to do. One small play we did, it had five characters and it had five writers. I recall my friends Abbas Shah, Tariq, Razi and myself as being 4 of those 5 writers and actors. Coincidently the Progressive Writers’ Golden Jubilee came about, so Feryal Gauhar (Madeeha’s younger sister), directed a play call Yahan Se Shehr Ko Dekho which was based on Faiz’s poetry. We went to Karachi; I can’t describe even now how amazingly well it all went. All the big writers were there, we couldn’t believe ourselves. From India, Pakistan. So that was our journey. What was Ajoka then? We travelled in third class compartments during our train journey to Karachi. And in Karachi we stayed in Baluch colony where a friend of ours had a small flat. We 12 guys stayed there during the course of the whole conference. Then we came back. Auntie Khadija was very interested in the group, she used to attend our meetings, and she used to write a letter to Madeeha every week to inform her about what was going on.

FAK: So she was involved in keeping Ajoka alive?

SMN: As a grandmother looks after the child while mother is away…

SW: Another thing which we used to do was to attend all the political functions, book launches etc as a team together… at Faletti’s hotel and elsewhere. So Martial Law was lifted in 1985 (even though General Zia ul Haq remained in power)–and it was Junejo’s government, so there was some breathing space for us. So we, Razi, Tariq, myself and Abbas Shah, mostly four of us, we used to go together and the people used to recognize us and say here comes the Ajoka team. So in this way we kept the name alive. So then we invited Feryal and Jamal Shah who were doing Exception to the Rule in Quetta. I hosted them, the entire team, all men, about nine of them. So they stayed at my hostel room at the UET, we put mattresses on the ground and for this I had to face opposition from the house tutor who was a Jamaati. So it was a strange thing for them that nine people from Baluchistan were staying at the hostel. And then imagine Feryal Gauhar, young, beautiful Feryal Gauhar of that era, driving to the UET in her jeep to pick them up! So there are so many memories…

FAK: Your struggle, challenges?

SW: Even though we got along with Lok Rehas colleagues after the split, some of them were our seniors, but there were some bad apples. We went to meet them to try and resolve our differences…And then another challenge was the people from the established theatres, it was difficult for them to digest what we were doing. I can quote some of them without naming them, saying things like “there can’t be any theatre without costumes and it is not theatre you are doing”, and “what is this what is that?” So had to work hard despite these naysayers to do it, to prove that our type of theatre can go on.

FAK: I want to interject, I love these stories. I think given insight into those early days what Ajoka was and the people involved, I think that the sort of challenges you mention continued after Madeeha came back from the UK, these were early years and it was again an anti-establishment theatre group and you had to find help where you could and you still continued and at that time Ajoka was a place where you tried to spread the message even with the help of street theatre. So it remained political at that level and then you went into villages and inner city locations. Those were exciting days as I am hearing from you. How would you compare those days with where Ajoka finds itself today? Because on one hand one has to evolve as Ajoka is today arguably the leading group in Pakistan, the leading theatre company. So it is no longer “alternate” or “parallel,” right? So there is nowadays the critique that the oppositional nature of Ajoka has changed. It is said that it is now part of the institutional structure which is exactly what it wasn’t when it started, in fact it was opposed to the established theatre. How do you feel about that? What is your own narrative about that?

SMN: It has never been part of any institutional structure fortunately or unfortunately. It has remained a group outside the mainstream politics and establishment politics. It has always done plays which critique the establishment, whatever has been the ruling political or social ideology, whatever challenges the society is facing whether it is extremism, police brutality, corruption or dictatorship. I think the major change took place when Ajoka discovered the Goethe Institute or the Goethe Institute discovered Ajoka. That was in 1985. The play was Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle, adapted as Chaak Chakkar, which we are now reviving on the request of German Embassy. Before 1985 Ajoka was just a hit-and-run theatre group; now it got a place to rehearse and perform…

FAK: This is being what Sohail was narrating too…

SMN: We were performing without any government approval and all doors were shut us. We had to perform in factory yards, streets, house lawns.

FAK: So basically it was a poor theatre, in the manner of Grotowski…

SMN: That’s right, and then somehow the Goethe Institute allowed us to use their back lawn which was not of much use to them except for occasional tennis. In this way Ajoka got a base. We moved from Khadija Gauhar’s front lawn to Goethe’s back lawn! Initially Ajoka performed all over the Goethe Institute building, their terrace, their rooms, their lawn. Then they were allowed to build a small mud stage in their lawn where you have performed in that first production of Barri in 1987.

FAK: I remember that well…

SMN: I think that was a major change which allowed Ajoka some stability and a chance at experimentation and audiences also became regular and more committed. The audiences did keep changing, from a performance in Lahore Cantt to a performance in Kasur, there were bound to different audiences. one urban and upper middle class, the other a small town with poorer folks, less educated, shopkeepers etc. This phase continued for up to a decade and a half I think. The next stage began after the restoration of democracy that led to opening up of Arts Councils halls for Ajoka. Now Ajoka started experimenting in sound and lighting and set design. So these were the three major stages which allowed Ajoka to develop aesthetically, artistically as well as politically and socially, from informal urban spaces and foreign embassy grounds, to urban working-class locales, to finally, government venues like the Arts Council halls. Earlier on Ajoka’s work was more focused on the dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq. When Zia disappeared, so too did many theatre groups.

FAK: Because their raison d’etre was no longer there?

SMN: Their target had gone. The people who had been interested to serve only a political cause now returned to their parties, their media, their trade unions and carried on in that way, but Ajoka targeted the system as a whole, the mindset of citizens, and all the new challenges which were taking place under the guise of democracy, in the form of religious revivalism. Our mission was to keep on challenging that mindset and the societal and ideological structures enabling it, and that was how Ajoka’s role, their relevance in the society went on evolving and adapting to the changing times.

FAK: Can you talk about the fact that here was a theatre company that came into its proper existence under a woman’s leadership, who has been its founding director, handling and managing largely a cast of male actors and clerical staff, yet doing plays which had to do with changing the patriarchal mindset that governs gender dynamics in the society. I have written about it as you know[7], and called it a feminist theatre company of Pakistan, but do you think that it was/is a feminist theatre? If so, then why haven’t you succeeded in getting in more women in it, or has that number increased from the early years? In other words, has Ajoka in itself created a climate where women can come and perform on the stage? Or has the company remained male-dominated in a certain way, despite Madeeha’s dynamic presence and leadership…

SW: For this I say, we have to look at the time and environment in which Ajoka was created like what was the situation in which regular performances were happening on PTV, for eg, with all its restrictions (being an organ of the state). In those days all progressive artists, including women like Madeeha were targets… And the status of the women in those days in 1980s under Zia ul Haq’s Islamist regime was really slipping backwards. So we have to salute Madeeha’s achievements in such an environment, because it is a fact that if someone who is such a staunch feminist and strong woman had not been in charge of Ajoka theatre, we would not have been able to achieve even half of what we achieved in terms of highlighting issues dealing with the oppression of women and minorities. At least there was this visible symbol — the person in the lead position of Ajoka–who was a woman. And from time to time we were able to achieve other changes as well. We were, for example, able to attract other women to join the group. But the more significant change was what happened in the attitudes of the male actors. You can see how many of their wives and daughters got involved in Ajoka theatre as actors, singers, dancers over the years.

FAK: That was my next question, do you think Ajoka has made a dent in the social and cultural attitudes including attitude to the women participating in the performing arts, among other things. So you, Sohail, are saying that it has, and this change would not have happened without Ajoka’s lead? Shahid, your thoughts?

SMN: Firstly, yes it is a feminist theatre group, it was even in those early days when everybody dreaded the word. Because feminist is not only about women, it is also about changing the mindset, the patriarchal way of thinking of most men in our society. I myself have been long designated as a feminist playwright even in my Amnesty days when I was working in London for Amnesty International. I was the one who was chosen to represent Amnesty at the UN Decade of Women’s conference in Nairobi in 1985. There was a big debate in the Amnesty secretariat why a man was being sent to represent Amnesty at the women’s event. It was finally agreed that it was more important to see what you say and what you do than your gender. Almost all of Ajoka’s plays are related to gender issues in one way or the other. They present women’s characters who are forceful, strong and defiant. So through its plays it has touched every aspect of gender discrimination in our society. Our plays touch on themes of honor killing, family planning, women’s education; we have performed plays on women’s right to choose a career, to choose their partners, to choose how to dress – to wear a burqa or not to wear a burqa – all these issues have been addressed. But the other thing is that in Ajoka women have always had a strong presence. It was the only group where young women did not have to worry about being discriminated against or harassed despite late night rehearsals, tours to other countries, etc. That’s why people would send their daughters and their wives to work with us.

FAK: So it was a safe space for women…

SMN: That’s right, and it has remained a role model, it has inspired women in other capacities as well. Ajoka showed that it was possible for women to participate in theatre, even lead it. Ajoka has given respect to its female actors while promoting the cause of women’s emancipation through our plays.

FAK: That brings me to the larger political question about where Ajoka is headed. Your narrative of the evolution of Ajoka tells us that more and more women are being allowed to come and join Ajoka including wives, daughters and sisters of Ajoka’s male activists; certainly the most recent production of your new play Charing Cross which I saw here in Lahore recently, bears out the fact of many women actors in Ajoka. This might not have happened in any other theatre company, right? Now, was gender related to the question of class? As far as I understood Ajoka has been a group which always encouraged people to join it from Lahore and its surrounding areas, and most of those who joined the group were not from the elite classes here. So in terms of an egalitarian absorption of those members into the group, how much would you say that it has happened successfully? And do these long-term members also participate in some decision-making, or sharing in director or playwright roles at all? Or it is still a company which is owned by Shahid and Madeeha with you two making all the artistic and financial decisions of Ajoka?

SMN: Well frankly speaking, the answer to your question is both yes and no. There are very few directors, male or female, who can present social issue-based theatre in an entertaining manner, and there is hardly any writer here who can write for theatre with a strong social content that is also entertaining and aesthetically crafted. There are not many opportunities for people to train in these crafts, nor for people to be exposed to high quality theatre, world theatre, and also because of a lack of government support for this type of work, we’ve basically just had to keep going with Madeeha and me at the helm of the company. Unless you get some sort of support from the corporate or government sector you can’t survive as a theatre company. We too have rejected many temptations to live a more settled and financially secure life. So that factor of our control is there whether you like it or not. But that too doesn’t mean that we could have pulled it all off on our own. The team spirit of Ajoka and the audience support are very important factors in our success and longevity. Most of the people involved as actors in Ajoka have been coming and going unfortunately, because theatre was not something which could sustain people. But since Madeeha and I and our family had become wedded to Ajoka—our older son Nirvan has been performing with Ajoka since his childhood and now even helps direct plays occasionally–so for us, it was quite a different thing. I was carrying on too with my job in PTV as a producer, and for other people they had to find jobs as well, they had to get married, some of them would go in to different fields. I am sorry for the loss of some excellent people, some of them female actors, who had a lot of potential when they joined Ajoka but then they had to leave because of social factors and family reasons. The people had been coming and going and it is interesting to see that a lot of women had come from middle and upper middle class while men had come from middle and lower middle class. And there was a mixture of these classes and interaction of these classes on Ajoka platform which was very interesting. They were all anti-establishment individuals, they were all anti the rich classes of our society, even those who came from those classes themselves. When you see the list of women who have appeared in Ajoka, quite a few of them actually were very critical of their husbands and their fathers as portrayed in our plays.

FAK: They led more or less progressive lives, at least to some degree….

SMN: Yes, there was a mixture of people here, but you had to have progressive views to begin with if you were interested in joining an outfit like Ajoka. A few of them were exposed to theatre abroad, western political theatre. Perhaps they could see that Ajoka was the only theatre group which was providing entertaining theatre yet with a strong social purpose. New groups keep on coming up trying to follow in our footsteps, and now you get more highly educated women, with MSc, MBA degrees, and teachers as well as other professional women who come to us and want to work for Ajoka. Some of them have talent, others don’t. But they are all very ambitious …

FAK: So do you see Ajoka continuing in the next generation of Shahid and Madeeha in terms of your children, or will it be taken up more democratically by some of these others? Will it continue or finish, once the current generation of original Ajokan actors, director and in-house playwright is gone?

SMN: As far as the main body of actors is concerned, they are there. The main challenge is to find new actors to replace the ones who leave, and we are moving towards diversifying the field of direction as well. So we have some people who have some potential for becoming directors. I think more challenging is the field of playwriting.

FAK: Have you not held writing workshops, a possibility you might think about?

SMN: Madeeha has been a creative director and a hard taskmaster who has been passionate beyond words… she wants to carry on, she wants to perform, she wants to be there, every year with new productions, every month we should have some new activity. So it is a small group with limited resources. So it has been exhausting, and for me as a writer, I have been in other kind of writings also. So writing for Ajoka and organizing workshops which can result in good talent and grooming talented writers, it’s a lot to take on, a lot of pressure, and frankly, we just haven’t had the time, energy, resources to devote to this side of our work. Otherwise I would love to have some time to focus on writing and developing that craft in others. It is a very different craft. We have good writers for television, for films, for another type of writings but for theatre and for the type of theatre that we do, it is very challenging thing to maintain the balance. Writers who are ready to sacrifice, no fame, no money and ready for a lot of hard work.

FAK: Any thoughts to add to what we’ve discussed so far, Sohail?

SW: Myself being part of other feminist organizations like National Commission on the Status of Women and worked here myself, always I’ve been thinking in political terms, I don’t think that we have succeeded that much on that front—changing the social and political culture at large. My measure is slightly different. I say look at what Ajoka is, what’s its composition, from one end to another put the 33-years history on the table and then tell me and compare it with any other organization in terms of socio-political and class relevance and diversity of faiths. Tell me a theatre group which has significant number of Christians, Hindus, Sikh, and people of different educational levels – from ones who read only newspapers to those who went to Harvard, to Warwick or have Columbia and London University degrees; compare this list and the co-existence of so many different folks to any other similar outfit in the country. So my measure is that Ajoka has succeeded in creating a space with all these class, social position, faith, urban, rural, you name it—where all these diversities have been represented and all these people have worked together for over three decades. Do they interact when they are performing? No. They interact in a variety of other ways. Do they socialize with each other? Yes, led by their director, Madeeha, whether they live in a one room house or live in a fancy Bungalow. We used to make it a point to visit people in their happy occasions or their times of grief. So I measure the success of Ajoka’s experiment from that. Obviously, there have been too many challenges. There have been too many tough hurdles to overcome. Ajoka of different times – 80s, 90s, 2000, 2010 and now in 2018, there have been too many expectations which put us under so much pressure. Just as we finish a production we are asked: “where and when is the next one?” In Ajoka’s repertory the number of plays is astonishing by any measure. IPTA’s repertory had 15 or 17 plays, this was the biggest theatre group we grew up hearing about[8]. Is there any other theatre group which organizes a theatre festival of its own and performs five different plays on all the five days of such a festival?

FAK: And what is the repertory right now?

SW: We have original and adaptations totaling approximately 50+ full-length plays. Which group finishes a play in a festival in Karachi or Islamabad or abroad, then rushes to Lahore because there is a special occasion in a slum and they have to perform there?

FAK: And this diversity of performance venues and audiences addressed has continued?

SW: The day this aspect of our work dies, then there will be a big difference in Ajoka, then it will mean the ideology of Ajoka has changed. We will be worried! But to go back to your question regarding the need for more playwrights and directors to be groomed in Ajoka…that certainly has been an issue we have debated. Madeeha has always encouraged some of us to take on director role, and I think in the early 90s we had plays where younger people directed.

SMN: Savera, my daughter has directed for Ajoka [9] as well

SW: We have actually held writers’ workshops in different parts of the world like Nepal, India, communicated with the writers to encourage them to keep writing. Coming on to when Shahid and Madeeha got married in the late 1980s, I went to Jang Forum or somewhere and folks asked about it, and in reply I said my answer would be a bit selfish. They asked what is your answer? So I said I wish them both all the best and a happy life because it is good for Ajoka! I said it was a selfish wish, because it gave us an in-house writer and in-house artistic director. Why have Shahid’s many plays become popular and more than that, long lasting? Because those were written with an idea to be performed in the modern theatrical style that Ajoka was developing under Madeeha’s guidance, and there were discussions amongst us Ajokans while these plays were being written.

FAK: You were part of the process while these are being written with director and actors all contributing to the process?

SMN: Yes, that’s right, and our discussions were conducted with performance in mind. Generally, Drama is not considered as a performance art, writers would write profusely with literary and subjective kind of script just like fiction or poetry which has no sense of communication with the audience and no visualization that how will it appear on stage. For me the benefit was that I knew that a few weeks later it will be performed, so I have to foresee that what are the resources and what are the visual and performance requirements. So that kind of discussion also led to our plays’ ability to reach our audiences more effectively.

FAK: It interesting what you’re are saying, Shahid, because you are not formally trained as a playwright and you have developed your craft really through the process of trial and error. Isn’t that correct? But now you have accumulated certain expertise which I think would be a shame if it were not passed on…

SMN: I am happy to talk to interested people whenever I am invited to universities to talk about it. But there is nobody to follow it up in a sustained manner. The institutions are not interested, universities and government institutions. So that’s why whatever we can transfer is not put into a deliberate process…

FAK: So do you see any of that changing over the years? After all there are now places like NAPA (National Academy of the Performing Arts) in Karachi, so are they taking up things like playwriting etc there?

SW: Many things are changing. As Shahid was saying sacrifices are needed as generally speaking, writers get no money, no fame. But to get back for a moment about your question regarding the continuity of such institutions one thing which emerges as a factor is that Ajoka is still lucky that many of us who are still involved with it, have had long years’ association with it. At different times in our lives, there have been various levels of engagement. Like in my early years I was a student and once I had to miss my exam paper and my late mother in her simplicity had to call Madeeha and say to her that he listens to you, tell him to concentrate on his studies. Madeeha used to come to me and say your mother called, very sweet, I like talking to her but it is the usual message, listen from one ear and let it go out from the other! And then the question of resources. When we were doing Barri, if you remember, Madeeha came to me one day just when performances were about to start, and asked me what were we doing regarding rounding up a good sized audience, and I told her that since morning I had been on the motorbike selling 10 rupee tickets in the town—this was what somebody in a lead role like me was doing!

FAK: Well, you have come all the way from that humble beginning to a position where Ajoka pays actors. Isn’t that a success story in itself? How did you manage it?

SMN: It is not a guarantee that we shall continue to pay to actors. We pay when we can and it depends whether there is money to be paid.

FAK: Is this the money you generate from your fame and from NGOs?

SMN: Sometime we get support from the international institutions which are interested in supporting the secular and democratic voices and then their position changes literally every year. Today Pakistan is the focus, next day it can be Iran or Afghanistan…

FAK: So it is not a reliable source of funding?

SMN: … or Guatemala, we have seen it happen many times. Norwegians were very supportive, suddenly their policy shifted and they disappeared. Then Americans got interested in specific projects for one year, two years, then they would say we don’t know when the next time will be when the grant is available…

FAK: So you must be continuously worried about the sustainability of Ajoka right? What steps do you take to keep it going?

SMN: We save money when we have the funds and put it in deposits with a good rate of return, and when we don’t have funds we withdraw from our reserves. Sometimes there are individuals who are happy to donate. Sometime there are significant donations. We have friends of Ajoka who donate and contribute every year. Then during the last few years, the government of Punjab has agreed to pay us although a very modest sum, a small amount which might not be good enough for one play but this is something at least, and a good change.

FAK: What about the audiences, have you been able to successfully create paying audiences?

SW: It is a bit complex. At Alhamra Arts Council we don’t charge a fee because from collaboration point of view we get nominal payments from them and make the theatre totally free. If we put tickets, then we have to deal with excise and taxation department and have to get no-objection certificate from them at every play which is a royal pain because of the bureaucratic hurdles. These days we have submitted an application to get a permanent NOC (No Objection Certificate) for our Alhamra performances. But it will be very difficult for us to do that because we don’t have any kind of management. We have our Friends of Ajoka list who get intimation through word of mouth and invitations through post and they pay annual subscription rupees 5000; we shall be increasing that amount soon. So much needs to be tapped but these things happen a little bit on marketing style. We are short of that manpower. How many tasks…there are two or three workers like me. I didn’t go for a full time job and used to go freelance from the beginning so that I could give me time to Ajoka. Some of my other friends were also like that. Naseem Abbas used to live in a single room in Ajoka office with his family. It was in a way a support for him but on the other hand he was available for anything 24/7. So some of us could do that, have done so, but that can’t be endless. We need very basic support. Like Kami is here for long time, Nadeem Mir is for years and they are more here than they are at their homes. Similarly, I spent many long years like that. But of course we need more people with that attitude so that we can survive on bare minimum. But the problem lies with the larger society. Compared with the Indian counterparts, the theatre groups there, they live on meagre resources too but there is an environment in the society that buoys them up, respects them. The society we live in here is a neoliberal society which is so consumer ridden that people can’t survive on basics. There are so many pressures. We are outcast from our families, many of us. You were asking about women. Can I tell you how many boys/young men are in Ajoka whose addresses are known only to me and one other person? Their families didn’t know that they are performing in the theatre, right, and so they need to keep their residence secret for fear of reprisal from their families, just like the women. We have to sacrifice so much just to keep going….

SMN: The Americans keep on asking Pakistani government DO MORE to fight Taliban and here Madeeha keeps asking us to DO MORE (laugh) both the parties are in-satiable in appetite! What we now need to do is firstly, to have a good Ajoka-based archive, we have so much to preserve – 60 plays and workshops, festivals and scripts and experiences of traveling in the country and around the world and this has to be preserved for posterity and for researchers. The second thing is that we should have some kind of endowment fund which can make itself self-sustaining. These are the things we need to do but in this society there are not those forces which will take the initiative. We are so consumed by actually doing theatre that these other important matters need to be attended to away from the theatre. Perhaps we can invite some interested and committed people to start the archival process as we invite people to act in our plays. Maybe we can have some folks from the colleges and universities…

FAK: Yes, colleges and universities both local and from the global north should be asked to get involved; maybe digital archiving is the way to go…

SW: A few days ago I was talking to Shahid that our music, very rich music in Bullah, Dara, even this Chaak Chakkar, so much original we have in these plays, yet we have not been able to record it, we are not able to market our CDs and generate money from this resource. On documentation side, students have done theses on Ajoka, how many plays are taught in India, educational institutions. But we haven’t been able to monetize any of this activity….

Ajoka Production of Bullah.

SMN: Perhaps what we need to do is to have some marketing input …there is such goodwill for Ajoka everywhere. I was recently in London to speak at a development conference at the London School of Economics. Can you believe that about a dozen young students from Pakistani origin, they came and they told me they were great admirers of Ajoka or their parents were. They knew a lot of our plays and they were discussing those plays in their classes, or amongst themselves. So the goodwill, the impact has been there; what we will need to do is that we should have one separate assignment or project for archive and one for building some kind of endowment fund going forward…

FAK: Both are very important steps to take so that Ajoka’s work can continue. What about exploring a digital archive, there are a lot of projects going on in the US like the one coming out of the University of Berkeley which has been building a digital archive of Partition stories.

SMN: I think for constructing and then housing an archive we have to get some partners …

FAK: There is some funding available for what they call digital humanities projects. I think that’s what you want. Actually any archive nowadays should be digital because only then can it be available to everyone.

SMN: And then it is safe too.

SW: Can you look into it where you are based?

FAK: One should look into it yes, I would love to.

SW: One should put in a proposal that this is what Ajoka wants to do, to collate our things, our copyrights. Gone are the days when we used to let people, I am not naming them, the people who used to come and videotape our plays and later they were raising money from those videos for their own projects, and Ajoka never…well, nowadays everybody wants its ownership and copyrights, so Ajoka should also have it. If they are doing Partition stories, then Ajoka’s plays must be included in that archive…

FAK: Yes, especially as part of the mission of Ajoka has been to do this kind of cross-border solidarity work with Indian cultural activists. It has raised some eyebrows at certain points that Ajoka is pro-India … and on the other hand it is the need of the day, you have done all that. Is that an important part of your continuing mission?

SMN: Yes, peace has always been a major focus for Ajoka, peace within your own society and peace in the region and in the world. With Indians we share so much in terms of our cultural heritage and art, our social concerns, language, heroes and we got so much inspiration from Indian theatre groups because they were better organized, and there were so many of them all over India. So right from Calcutta to Mumbai, Delhi and India Punjab, so this was natural that we wanted to interact more with them and learn from each other and perform for each other and we have done that very successfully. This is promoting the cause of peace even in the most difficult and more tense times when our governments were in an almost war-like situation. We carried on with our message. Yes, the intelligence agencies on this side mainly, were suspicious and on the other side of the border also, they were suspicious as to what is our objective. They tried to follow us, track us, harass us, question us. Like when we would go to get visas from the Indian High Commission in Islamabad, invariably we would be stopped and questioned. But I think now they have sort of given up. Firstly, they see that they can’t stop us. And secondly they acknowledge that we have no other hidden agenda, they can see we just want to promote cultural interaction and promote the cause of peace and it amazes me that the myopic Pakistani establishment has not seen the potential of, or capitalized on the potential of, performing arts, theatre, music to wage peace, not war. We have been welcomed, warmly welcomed in India even by parties who are rabidly anti-Pakistan, anti-Muslim, like the right wing of BJP, Shiv Sena. We have gone where we have seen BJP protesting our performance and at the end coming and hugging us, congratulating us. The nature of our plays is such that they appeal to everyone because they appeal to the humanity in each one of us. In Bangladesh, our performance was boycotted by the national liberation struggle veterans who were quite active in theatre; they boycotted our performance and next day they came to us and said they were sorry to have missed our performance and then they withdrew their play from the festival and allowed us to perform again that day; that’s how we built friendships which have continued until today.

FAK: You were the first theatre/cultural activist to apologize on behalf of Pakistanis for what happened in the terrible war of 1971 when you were representing Ajoka at an event…

SMN: Yes, we were the first theatre group after 1971 to go to Bangladesh and perform and the first thing we did was to go to the war memorials…

SW: We went to the Martyrs’ Memorial where particularly several academics had been killed. Some of the Bangladeshi people I know through various connections were not there on our first performance, but they read the coverage and were there for the second performance.

SMN: There was a well-known actor and director Sara Zakir, her brother was killed during the liberation war. They were very involved with the liberation movement and in the liberation museum, she is one of the main leaders. So they were those who boycotted us initially, but then came back to see our play when they heard we were not jingoistic but rather, critical of what our government had done…

FAK: Didn’t she later collaborate in directing your play on trafficked women, Dukhini?

SW: She was the director in fact.

SMN: And then when we performed Dukhini in Chittagong, there were protesters outside and she was the one who went outside and challenged them brought them in telling them that this was the group which was working with us for a common cause and you have no reason to protest. So this is how theatre can change things even in most difficult circumstances and it can open roads to healing.

FAK: I just want to end with one last thing, tell me, share with me perhaps each of you a favorite play and one fond memory, and maybe a hope for the future as well?

SW: One fond memory from early years, as I described we were trying to establish ourselves, it was Faiz Mela [10]happening several years after we began our struggle, and there was a session on the literature of resistance and Ajoka got named in that session. I was sitting in the audience and I suddenly woke up, “oh now they are recognizing us! We are finally part of the literature and art of resistance!” That is now a fond memory when I look back on the 34-years history of Ajoka. You could ask me about the cast of a 1994 play and I would be able to name them, but by now we have done so much, just look at this wall, all those posters of our productions…all reminding me of happy times, of what we’ve managed to build despite so many difficulties; and at this moment my ardent hope is that my director comes back to good health, oh when I remember her energy, her unflagging passion (he tears up; pause; then continues) and Shahid’s energy in his own style, he has written countless plays, imagine this: I am driving a car, he is sitting next to me and writing a play; we are going to Nathia Gali for a workshop, we are driving on the old Grand Trunk Road, it is a Suzuki FX and Shahid is writing with a notebook on his knees! One day we were going somewhere and he was writing a TV serial based on our play Barri; he completed an entire episode as we traveled! He writes like that. Ideas that he generates in his mind just come tumbling out on paper. We were watching tennis together and he asked me a question “what do you think is the salary of a grade 19 officer?” Later I learned that he was thinking about the situation of a character in a play. There are too many fond memories. Why do I still come to Ajoka? There is bad news all around, I come here and sit here for some time quietly. It re-energises me and then I go back to whatever activist work I am doing with renewed faith, because to remain ideologically true is the biggest challenge in this period. And off and on encouragement from Shahid and Madeeha, one phrase here or there, makes all the difference and keeps me going. The other day there was a launch of Shahid’s new collection of plays, Anni Mai Da Suffna and while speaking there Shahid recollected that “Sohail was also among those of us who were dreamers.” That meant a lot to me.

FAK: Shahid?

SMN: Well, due to some reasons Bulla is my favorite play which kind of revealed itself to me when I was in London with Amnesty in 1986/87 and saw a translation of Bulleh Shah’s poetry with the foreword by noted critic Khalid Ahmad. In passing, the reference that when Bulleh Shah, the Mullahs kept on debating whether his funeral is permissible under Islam or not, and that they continued to debate this for three days, that’s when suddenly the whole play dawned on me: the brouhaha around Bulleh Shah’s body, his trial, and struggle. Somehow this play has really transformed people, actors as well as audiences. Actors have become Sufis and poets! In one case in Indian Punjab, where we were performing the play, after the performance an old man came and told the actor who was performing Bulleh Shah’s role that my grandson is not well, so can you blow a blessing on him? The performer said Baba Ji, I am only an actor not Bulleh Shah, at which point the old man started crying and insisted that blessing should be blown and finally the actor had to do it. The old man was satisfied. Before going away, he said, “You are not an actor, you are Bulleh Shah’s re-incarnation.” So that is how sometimes theatre and theatre’s stories are seen by the people as re-incarnations or re-living of the great personalities and great events of the past, and this can effect positive change for the present and the future. Muzaffar Hussain, the Indian film-maker and event organizer, very much committed to arts, wrote a piece on our play which referred to this incident “When Theatre Becomes A Shrine.” So sometimes theatre does become a shrine and it can even overpower very strong regressive religious forces like the Mullahs and Muftis of Kasur where we also performed this play. In another incident related to this play, the powerful Gurudwara Parbandhak Committee of Sikhs, objected to the representation of one of the Sikh characters in the play – Banda Singh Bairagi–when we performed it India one year; they wrote against our play to the institutions and the parties involved with inviting us, trying to get the permission revoked. Yet, we were still able to perform but at one place we had to cut out certain scenes because of the pressure and that censorship actually caused such an uproar next day. The criticism from the media and theatre community and intellectuals was so intense against this censorship being imposed on us, that the Sikh community leaders couldn’t censor Bulleh Shah anymore. So this is how a theatre play can make a difference! Then there are also other plays of mine with Sufi themes such as Dara that I am very fond of, which was also performed in translation at the National Theatre in London.

Ajoka Production of Dara.

FAK: You have recently also started to experiment with some new forms and themes, for example your latest play I saw in Lahore…

SMN: Let me end with one more fond memory of a play I am really proud of, that is of a play called Ek Thi Nani in which Zohra Saigol and Uzra Butt both in their late 80s, were our stars and I wrote the play based on their life stories. They performed it in India at the Habitat Centre and it was the first time that the two sisters were able to perform together after a gap of 40 years due to having separated at Partition, and the emotional atmosphere, old ladies coming to watch the play with grey hair and white saris, hugging each other, was very moving. It was again a testimony that theatre could re-connect people after the wounds of Partition which not only separated the two sisters but two societies also. The play was performed again in the Prithvi Raj Theatre in Mumbai. That was the venue where Uzra Butt, Zohra Saigal and Prithvi Raj used to perform before the 1947 Partition. The members of Prithvi Raj Kapoor family were there when it was performed. The late great actor of Bollywood, Shashi Kapoor, was there too–he used to play the son of Uzra Butt in some plays during pre-Partition days. It was remarkable how they all were together again at the performance of Eik Thi Nani and how emotionally moving the atmosphere proved for all of them.

FAK: That’s a lovely testament to the power of theatre to heal trauma and reconnect us across all sorts of borders and divides. I want to conclude with your recent experiment with a different form of theatre which I think is very interesting—combining elements of fantasy with realism in a kind of postmodern pastiche of the past and present of Pakistan. This play, Charing Cross, had a whole other feel to it due to a different kind of performance style from the usual Ajoka plays, and it is written a little bit differently from your other plays as well. Do you want to say something about that? Maybe just a few words, commenting particularly on its rather forceful endorsement of a particular political message and political party of Pakistan—the PPP. Madeeha wasn’t too pleased about what she perceived as a play that she said to me could be seen as a propaganda tool for the Peoples Party…Ajoka has never aligned itself to any political party according to her.

SMN: Well, it doesn’t endorse any present-day political party because the present-day PPP which you are referring to has nothing in common with the political party as represented in the play. And secondly, it is not really about a political party but a certain ideology, a certain thought, a certain hope which was in the air in the 1960s and 70s when people thought that the socialist revolution was around the corner, that things will change and oppressed classes will become the rulers. This euphoria as history has shown us, was based on thin ground, but this period of the 60s, 70s and 80s in Pakistan was influenced by an international wave of the student revolutions of the late 60s and all that. It was actually more of an autobiographical account of my own experience, how I got involved in student activism, youth activism and the hopes which we had and the passion which we shared, and the heroes we had (like Z.A. Bhutto)– and how these idols and hopes were shattered and how the counter-revolutionary forces, extremist forces came in, such as consumerism, globalism, the market economy on the one hand, and religious extremism and terrorism on the other, how they combined forces and then how they separated or appear to have separated from each other. So this play is basically a re-living of that history and like it or not, two major incidents take place in the play which are based on factual events that have had a profound impact on our political landscape, and those are the judicial execution of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and then the extra-judicial execution of his daughter Benazir Bhutto. So these two events are very dramatic for theatre and have exerted an influence on the shape and psyche of our society whose impact cannot be underplayed.

FAK: And you link all of this back to colonialism…

SMN: There is a colonial legacy of course, that we are still grappling with, we have hardly changed that system, and the ruling classes have not changed. At the same time, there is an undying hope of resistance and the struggle continues …

FAK: … which takes different shapes in different times…

SMN: …yes, how the beast of oppression, and resistance to it, both keep changing their faces, even though the underlying realities remain the same. But I’m presenting serious themes in a light-hearted manner, through song, dance, satirical humor, dream and fantasy…. I think it is a fun play! Yes it is bold and more politically direct than many of my other plays. But I think this was the play which was in my head for a long time, wanting to come out. I couldn’t hold it in any longer.

FAK: I am glad you didn’t! Thank you very much Shahid and Sohail, for this insight into the genesis and history of the Ajoka Theatre Troupe, and of course, in recognition of its leader Madeeha Gauhar’s extraordinary contributions to it in particular, and to the cause of theatre in Pakistan in general.

IN MEMORIAM: MADEEHA GAUHAR, FOUNDING DIRECTOR of AJOKA 1956-2018

A Personal Note:

Within a month of the above interview I conducted with Shahid and Sohail in the office adjoining Shahid and Madeeha’s residence, all of us knowing that “Mad” (as I teasingly called her), lay upstairs in her bedroom battling out the final stages of her war with colon cancer, her body finally, reluctantly, gave up the struggle. Her spirit, however, will remain fiercely alive for those of us who have been privileged to witness up close and personal, the incredible journey of her life.

I have known Madeeha Gauhar (variously nicknamed Mad, Maddy, Aliki by her friends and family)—virtually all my life. Born of a union between a father who hailed from the fiercely independent-minded Pathans of the northern regions of Pakistan, and an equally strong-willed mother who had grown up in South Africa and who, as a journalist and writer was a fierce critic and opponent of apartheid, Maddy undoubtedly inherited both the stubborn will from her father’s side and a commitment to social justice and literary temperament from her mother. She was a few years my senior in school, and like so many others, I was very enamoured of her incredibly strong and forceful personality and acting chops as she dominated the stage in various high school productions at our first alma mater, the Convent of Jesus and Mary in Lahore, and later, at the Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore, where I still remember her as a dazzling Ariel in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Her performance as Viola in the Alpha Players’ production of Twelfth Night, performed on a stage erected in the back lawn of the famed Punjab Club, is another memory that doesn’t fade with time—I can no longer decide whether that mixture of sweetness hiding an iron will was Viola’s character or her own! So then, to share the stage with her some years later in college in A.A. Milne’s The Ivory Door was a treat, an honor and a nerve-wracking experience all at once; the seriousness she brought to the craft of acting inspired the rest of us to take it seriously too, and to work hard at what we initially thought was going to be a walk in the park. She taught us all to respect the theatre and to this day, I haven’t forgiven my parents for not permitting me to join her first-ever directorial debut when she struck out boldly on her own to direct Lorca’s The House of Bernarda Alba on the lawns of Kinnaird, after the faculty director of annual plays at Kinnaird had rebuffed her suggestion that we do Lorca’s play as our official annual production that year. Well, Madeeha, with her anti-authoritarian streak and not one to be deterred from anything she set her mind to do, did the play as a student production in the outdoor amphitheatre—and her rebellious offering utterly eclipsed the official play that year!

Shortly after General Zia-ul-Haq took over as military ruler of Pakistan in 1977—and after having enjoyed a memorable year as a first year Master’s student in the English Department at Government College, Lahore, in Madeeha’s company (she had joined the program after having been away in China for a few years on a Chinese language program)—I left on a scholarship to complete my Ph.D. in English in Massachussetts. During the years that followed my departure, Pakistan suffered a lot of hardships under the authoritarian rule of Zia, who began ramming unconstitutional laws through parliament to curtail the freedom of women and of religious minorities. In keeping with the spirit of resistance that defined her, Madeeha started the theatre group Ajoka as a cultural arm of the political Movement for the Restoration of Democracy in opposition to Zia and his policies that were helping to fan the fires of religious extremism. For her efforts she was rewarded by being sacked from her post as a professor at a government-funded university. Undeterred by loss of livelihood, Madeeha got a scholarship to the UK to study theatre formally, and upon her return to Lahore continued building and strengthening her theatre group, raising money for Ajoka through non-governmental organizations that were funding democratic and secular efforts like hers, as well as through audience support from those who were trying to resist the onslaught of religious extremism encouraged by the authoritarian government in power. Impressed by her efforts, when I returned to spend 6 months in Lahore with my newborn daughter at my parents’ home after completing my Ph.D. and prior to starting my academic career in the USA, I decided to join Ajoka. I finally also fulfilled my dream to perform on stage under Madeeha’s direction, in Ajoka’s maiden production of Barri (Acquittal), which we performed at the Goethe Institute for International Women’s Day, 1987. I later had the opportunity to perform the same role in an English-language translation of the play (done by another dear friend, Tahira Naqvi)—in Los Angeles a decade later.

My involvement in that play, and its imbrication within the movements for women’s and minorities and human rights struggles coalescing in Pakistan at that time, had a profound impact on my professional and personal growth. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that performing as the Sufi madwoman in Barri changed my life. My exposure to the Sufi poetry of Bulleh Shah, whose lyrics I learned to sing for my role in the play, brought me in touch with a part of my heritage I had neglected up to that point. And because of my involvement with Pakistani street and alternative theatre and the women’s movement, I decided to switch from doing text-based literary criticism in the early years of my academic career, to developing a feminist and materialist cultural studies approach in writing about Pakistani theatre work such as that of Ajoka (and other parallel theatre groups of the era, like Punjab Lok Rehas and Tehrik-i-Niswan). It is because of this work that my life has been full of passionate ideological engagement with the performing arts, both as a scholar and a performer, and for this rich turn that my life took, I will forever remain indebted to Madeeha who pulled me into the orbit of her theatre company and the women’s and human rights movement of which it was such a crucial part. She took part in protest marches against authoritarian rule, she was beaten up along with other women’s rights activists and jailed, but despite such experiences that may have deterred many others, Madeeha carried on in her determination to fight social and political injustice and repression through the power of performance. Plays she directed over a thirty-year career, have been performed all over Pakistan, India, Nepal as well as in Europe and the USA, with themes ranging from the plight of brick-kiln laborers (Itt), to plays challenging the patriarchal mentality which prevents girls from getting an education (Dhee Rani), to others that developed a Sufi aesthetic presenting Sufism as an antidote to Salafist Islam (Bulla, Dara), to plays that adapted Brecht to contemporary Pakistan, as well as dramatic adaptations of stories by leading progressive and revolutionary writers and poets of Pakistan such as Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Saadat Hassan Manto and Intizaar Hussain. Madeeha’s energy was unflagging in keeping theatre alive in spite of all kinds of financial and bureaucratic obstacles. For her contributions to the field, and in recognition of the tremendous labor and dedication to craft that turned Ajoka into the first Pakistani theatre company of renown throughout the world, she was awarded the Pride of Performance award by the government of Pakistan; she is also the first Pakistani to receive the Prince Claus award from the Netherlands and was also nominated in 2006 for the Nobel Peace Prize, undoubtedly in part because of her lifelong commitment to developing cross-border theatrical collaborations and exchanges between theatre activists of Pakistan, India, Bangladesh and Nepal, stressing in the plays of Ajoka , the cultural, spiritual and linguistic commonalities between the peoples of the subcontinent.

Despite a personal falling out with Madeeha that wasted too many precious years, I am glad and grateful that both of us were able to overcome our differences, and spend some healing, intimate time together in the final years before her life was claimed too soon by cancer in April 2018. During my last few visits with her this past March, she was still directing her actors who were rehearsing a play in the lawn downstairs from her bedroom where she lay writhing in pain and hooked up to an IV line.