Theatre Elsewhere: The Dialogues of Alterity By Sepideh Shokri Poori Arab Stages, Volume 8 (Spring, 2018) ©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications

The questioning nature of human beings has challenged theatre for a long. Therefore, more than any other art, historically theatre has been involved in sustained interrogation, reviewing and self-censorship. It is an art concerned with watching, thinking and experiencing together. It is the art that, according to Georges Banu, brings down the dominant power of Gods from the sky to the earth, “because surveillance is a holy, divine and unforgiving activity, and only belongs to God, who is present everywhere and is nowhere.”[1] Perhaps it is logical that we still assume “the world as a stage” because this grand spectacle was at the time under the gaze of Gods and now is overseen by terrestrial observers.

Nevertheless, theatre has preferred the horizontal observation to its vertical form which from top to down and has changed the “Wise Transcendent Eye” to sublunary tastes: Gods became human and a divine theatre was converted to a humanist one. Now we are in the amphitheater, with two groups of observers: spectators and censors (in societies that suffer from totalitarianism). The first one is satisfied with his human power and in the best scenario, s/he is an aware thoughtful person, while the latter seeks the power of the Gods and s/he is an unreasoning viewer. So, this kind of surveillance is normally followed by the revolt of the artists because humankind, according to its nature, hates being under the observant eyes, and when it is placed in the hands of the dictator, this becomes unbearable. The committed artist breaks his/her chains and shackles. Sometimes he/she has no choice but migration, becoming an exile.

In the dialogic space of theatre, how can art operate effectively in a new space and in another language? How can theatre discover a universal language through new performing methods? These are some of the questions that I want to consider in this essay. First, I will explain the word “exile” and some of the leading artists in this situation; second, I will consider the works of some Iranian artists in exile.

Exile

If we consider immigration as a voluntary migration, exile instead suggests forced separation. Etymologically, the word exile refers to distance, separation and “earthly life” versus “heavenly life.” According to the Greeks, exile meant to live outside the homeland, withdrawal from one’s birthplace, and implicitly the loss of oneself. This distinction between elsewhere and homeland, alien and domestic was one of the basic elements of Greek culture and its literature and mythology replete with examples of the hero’s journey. What is interesting about land and exile is the word Nostos, which means “returning” in Greek. Thus, the story of Ulysses in the Odyssey and his ten-year exile finds another meaning: forgetfulness or in other words “forget to go back home.” In part of the Odyssey we read that Lotophages (meaning the Lotus Eaters) fed some companions of Ulysses with lotus flowers whose taste caused forgetfulness. This amnesia was the concept of “forgetting the land” and was the basis of exile.

In Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh[2] (شاهنامه) we have also seen the theme of exile in which Siavash (سیاوش) seeks asylum in Turan (توران): Siavash who hates war and bloodshed went to Jeyhoon (جیحون), the land of Afrasiab (افراسیاب).

However, his situation is different from that of Ulysses; he has no companions, nor does he try to find forgetfulness. Instead, he looks for a land where he is safe from persecution, in other words, he seeks freedom.

It is important to remember that in mythology, the journeying hero, as an errant traveler, seeks sacred purposes; he suffers pain to achieve immortality, while in contemporary literature the search by characters or author is not to discover divine reasons but for a better life. Milan Kundera is an example of the exiled writers who has chosen France as his homeland. He not only deserted his birthplace but also changed the language of his writing. The best description about Kundera is from Vera Linhartova, the Czech poet, who says: “I chose to live where I want but I chose also my language, because any writer is not caught nor imprisoned by a language. This is an emancipatory phase.”[3]

Theatre

The word theatre implies observing. Performing art is an agreement with the audience; it is a live and ephemeral art, which finds meanings in the presence of others. Consequently, the experience of being in theatre is a time-space skill that can be followed by the critical ability of spectator. By this definition, theatre more than any other arts will be monitored and censored, because it can potentially serve and betray dominant thoughts and power:

“Theater in every period has the power to overthrow and has always been a cause of fear and apprehension for lawmakers. […] Theater, an art that arose simultaneously with the formation of the Cité, is the base of the social organization. For this reason, more than any other art forms in the history of the arts, it has been sentenced to censorship.” [4]

Now the question arises as to how the exiled artists who have different socio-cultural and linguistic identities can connect with the audience in another location? If, according to Aristotle in the Poetics, the dialogue is one of the six elements of tragedy, then how can theatre in exile achieve this important goal? To answer this question, first I will introduce some influential figures in the history of theatre and their efforts to create a universal theatrical language.

Métèque

Métèque in ancient Greek refers to someone who had settled somewhere else, namely Athens. With this description, the most famous métèque among philosophers was Aristotle. He was one of the first émigrés: A Macedonian who taught and studied in Athens. Interestingly, he was not given certain rights that were reserved for Greeks. For example, to own the school where he taught philosophy was impossible for him. This classification and lack of access to all the benefits of a free Greek citizen could also be seen in the theatre: only male Greek citizens, including middle-class men, women and the foreign visitors to Athens, were allowed to participate in theatrical occasions like Dionysian festivals.

Due to the events of the twentieth century such as the rise of Nazism, Fascism, two World Wars, the Holocaust and the increment of totalitarian regimes, this century experienced unprecedented migration and exile. In theatre, perhaps one of the most important victims of dictatorship was Vsevolod Meyerhold. He was a challenger of naturalistic theatre who emphasized biomechanics (physical movements and an iconic style of acting) and formed a new expressionist acting method. Meyerhold, because of his resistance against Stalin and social realism, was captivated and tortured in prison until sentenced to death. Meyerhold did not have a chance to go into exile, while some other artists, including Bertolt Brecht, feared a similar fate and chose the exile.

Bertolt Brecht and Dialogues of exiles

Know that he is still alive. Just this.[5]

–Bertolt Brecht, Dialogues d’exilés.

In May 1933 the Nazis burned all the works of Brecht in a public square in Berlin, though Brecht and his wife had left the country for an unknown destination. Exile for Brecht began in 1933: he first went to Prague, then to Vienna and Zurich. His next destination was Denmark and from there to Paris and a trip to London. By 1935 when the Nazi regime denied his German nationality, he went to Moscow and finally went to New York where he remained until 1936. Brecht’s next destination was California where he resided from 1941 to 1947. At last, because of McCarthyism, he was forced to flee the United States. He returned to Switzerland, but the Allies canceled his visa. He stayed in the Czech and Slovak Republics for a while and finally, after years of exile, he came back to East Germany in 1949 where he founded Berliner Ensemble with his wife. In 1950, Brecht acquired Austrian citizenship; he had been from 1935 in statelessness situation.

Brecht was able to write many of the world’s most important dramatic works in exile, such as: The Life of Galileo, Mother Courage and Her Children, The Good Person of Szechwan, Mr. Puntila and His Man Matti, and Dialogue of Exiles. Undoubtedly, Dialogue of exiles is the most concrete work of Brecht in which exile, banishment, identity, and abuse of power are discussed. The initial part of the book begins with these sentences which report the mental conflicts of Brecht in this forced migration:

“In this country, beer is not beer, but cigars are not cigars either, it is balanced; however, to enter the country, you need a passport that is a passport. The passport is the noblest part of the man. Moreover, a passport is not made as simply as a man. One can make a man anywhere, the most distractedly of the world and without reasonable motive; a passport, never. Thus, the value of a good passport is recognized, while the value of a man, however great, is not necessarily recognized.”[6]

Samuel Beckett, writing in another language

You must go on. I can’t go on. I’ll go on. [7]

— Samuel Beckett, L’innommable.

French was the language chosen by this well-known playwright rather than English, his mother tongue. Writing in another language means ignoring the Babylonian nightmare, having the power of choice, and forgetting the power of God that prevents you from creativity, emancipation and, liberation. The writer who writes in another language, an artist who creates in another language and a spectator who sees in the other languages, are all the eternal destroyers of the Babylonian Tower: they open their arms to diversity, multiplicity and alterity. In Serendipities, Eco says “It is obvious that tradition focused on the story in which the existence of a plurality of tongues was understood as the tragic consequence of the confusion after Babel and the result of a divine malediction.”[8]

Beckett lived in Paris from 1938 onward and after 1939 he wrote entirely in French. The war and his migration were important elements in his work. The succinct vision and the connection between life and death are some characteristics of Samuel Beckett’s theatre. Waiting for Godot, Malone Dies, and Happy Days demonstrate Beckett’s philosophy. By writing in another language, he frees himself from the limitations of the particular emotions that his mother tongue brings with it:

“In order to free himself from the oppressive, ambivalent and tormented relationship with his mother, he not only left her, as well as his mother-tongue English, but he also left his country to emigrate to France. Moreover, it was only when he learned French that he could write and create more freely. It was only after the death of his mother that he translated his writings into English, after having written them in the newly adopted French language.” [9]

After the post-revolutionary years (1979), many Iranian artists have been forced into exile or immigration; among them were Susan Taslimi (سوسن تسلیمی), Hamid-Reza Javdan (حمیدرضا جاودان), Reza Jafari (رضا جعفری), Soheil Parsa (سهیل پارسا), Bahram Beyzaie (بهرام بیضائی), Shahrokh Moshkin-Ghalam (شاهرخ مشکین قلم) and Niloofar Beizai (نیلوفر بیضائی). I propose to examine the effect of exile upon their work.

Susan Taslimi

Susan Taslimi, Medea, 1999, Sweden. Photo: BBC Persian.

Sussan Taslimi, who has lived in Sweden since 1989, uses Iranian/Oriental methods in creating Swedish theatrical work. In one of her influential works, Medea, Taslimi worked on the subject of migration: Medea was also an immigrant; she left her land and fell in love with his father’s enemy. The author reports:

“I approached Medea’s personage through the Eastern Theatre. In a narrative way. Using a few masks, I played every seven of the roles I played. I put all my strength in the language so that my audience understood me. There were practically no immigrant players on the stage of the Swedish theater at that time. I was probably the first one. Today, with the increase in immigrant numbers in Sweden, this will be normal.”[10]

The myth of Medea has a great power to adapt to contemporary questions: A Black Medea who stands against slavery, a feminist Medea who is the antithesis of Jason and the patriarchal tradition, the Medea complex which involves killing her own children, and a contemporary Medea who speaks for marginalized classes. Therefore, Taslimi’s choice of this personage is not without consideration: This migrating Medea who is not far from her performer geographically (in Greek mythology, she is from Georgia) was shown on the Swedish stage by combining masks and narration. This was an important representation that guaranteed the future appearance of Taslimi works in Swedish theatres.

Hamid Reza Javdan

The Japanese say that the mask is dormant when it is put down; it can be seen as a bit of inert matter that suddenly comes alive on the stage, thanks to the art of the actor. This is a magical operation, a transition from motionlessness to life, which creates very strong emotion. It gives rise to perhaps the strongest reaction that one can feel as a spectator, because something that did not exist, that was dead or asleep, begins to live. In English, the word mask gives the idea of something that hides, but for Noh theatre it means “the face that one puts on.” The actor in Japan’s tradition is generally considered as the most important component of the performance. Ariane Mnouchkine has stated that “It is true that an actor who believes himself hidden behind a mask is actually naked and helpless, because a real mask does not hide, it makes visible.” [11]

Hamid Reza Javdan is an artist who has been influenced by many different ideas and approaches. The first of them, Iranian culture, dates back to his childhood. The others, from Commedia Dell’Arte, Mnouchkine at the Cartoucherie, Noh theater and Balinese dance, taught him the art of stage, song, dance and mask. The audience could see him evolving on the stage as his storytelling skills enchanted their hearts. For Javdan the mask is a traveling companion. It is the guide of the actor; it is his master. The values it brings to the actor are beyond calculation. “The mask, you have to follow it. You have to know how to be behind it, just like the musician behind his instrument. You must be its servant and keep its expressions while you are wearing it,” he has said.[12]

Hamid Reza Javdan, Masks, 2018, Paris. Photo: Sepideh Shokri Poori.

Hamid Reza Javdan began his career in 1976 in Canada and then in the United States at the Living Theater. It was his mother who first engaged and seduced him with a simple mask bought from a market in Tehran; then in San Francisco he encountered Commedia masks, and at the Cartoucherie with Ariane Mnouchkine’s Théâtre du Soleil, he continued his career as an actor and director. In recent years he has focused on his own theatre company, Theatre Mâ, presenting works in collaboration with renewed artists from around the world. He has also had roles in many movies, including Syngué Sabour (The Patience Stone, 2012) directed by Atiq Rahimi.

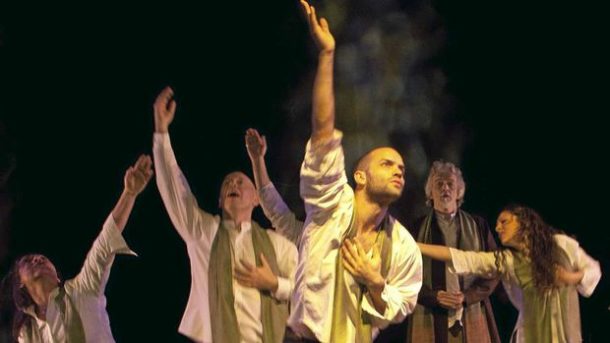

In the theatre, Javdan did a free adaptation of Attar’s The Conference of the Birds, which was performed in France and Germany. The play was named Un Jour dans la Prairie du Monde (One Day in the Prairie of the World, یک روز در مرغزار عالم, 2013) created along with music and masks. What seems important in this adaptation is the intercultural and universal aspects. The story opens in the Kingdom of China. One evening, Simorgh (سیمرغ), a legendary Persian bird, suddenly invades the sky. No bird has seen him yet. From his body falls a feather. The stir among the birds is so prodigious that their whispers run from the high mountains to the shores of the sea. After Simorgh’s departure, each bird seeks the meaning of this omen. The world of birds becomes divided into two groups: that of the Happy birds and that of the Unhappy ones. The Blessed flourish and improve, while the Unfortunates languish inexorably. Regrettably, since they cannot have access to happiness, the Unhappy sink more and more into frightful torments! So, some of them, reluctantly, decide to fly to unknown regions, hoping to discover some Utopia, a cherished freedom elsewhere. One day, all these birds hear the message from Hoopoe (the symbol of prophecy). Then, excited, they come to the Prairie of the World where the Hoopoe awaits them; he says: “The truth is in the cage, and the lie in power.” [13]

Yoshi Oïda, Earth and Ashes, 2012, Opéra de Lyon. Photo: Jean-Pierre Maurin.

For Javdan, the primary importance of the theatre is the actor because he leads the spectator to what the performance literally means. His experience as one who has also worked with Yoshi Oïda (in Terre et Cendres, Earth and Ashes, خاک و خاکستر, 2012) is very remarkable. In his various works devoted to acting techniques, Javdan has emphasized the actor’s body and his power in controlling it. He is a masked actor who tries to be invisible. As Oïda has explained:

“In the kabuki theatre, there is a gesture which indicates “looking at the moon,” where the actor points to the sky with his index finger. One actor, who was very talented, performed this gesture with grace and elegance. The audience thought: ‘Oh, his movement is so beautiful!’ They enjoyed the beauty of his performance, and the technical mastery he displayed. Another made the same gesture, pointing at the moon. The audience didn’t notice whether or not he moved elegantly; they simply saw the moon. I prefer this kind of actor: the one who shows the moon to the audience. The actor who can become invisible.” [14]

Reza Jafari

Although the intercultural theatre does not necessarily relate to the artist’s exile, it has a principle that can be equated with art in migration: the combination of cultures. In this cultural integration, what is most important is the openness of the artist, who is trying to find a new language for communicating with his audience. In his book, Theatre at the Crossroad of Cultures, Patrice Pavis compares intercultural theatre to the hourglass:

“In the upper bowl is the foreign culture, the source culture, which is more or less codified and solidified in diverse anthropological, sociocultural or artistic modelizations. In order to reach us, this culture must pass through a narrow neck. If the grains of culture or their conglomerate are sufficiently fine, they will flow through without any trouble, however slowly, into the lower bowl, that of the target culture, from which point we observe this slow flow; The grains will rearrange themselves in a way which appears random, but which is partly regulated by their passage through some dozen filters put in place by the target culture and the observer.”[15]

Here we can see the values of contemporary intercultural theater, trying to adapt and combine styles, techniques and diverse theatrical ideas. This is a form which attempts to create a constructive relationship with contemporary audiences.

Reza Jafari started his theatre career in Iran, before the Islamic revolution, in 1974. He came to Germany in December 1989 and was immediately involved in theatre work for children and adults. Jafari has been director of the Chaos Theater since 2004 in Aachen. In his company, he tries to use the people excluded from society, because he realizes that these young can find their identity through theatre works. “There were many who were convicted of crimes and sentenced to prison, but after 200 to 300 hours of work in this group, I have seen the impact clearly” said Jafari in a 2017 interview.[16] One of the main goals of the Chaos Theater is to gather actors from different nationalities with different colors, languages and beliefs, because what is important for its director is not the color nor the linguistic abilities of each actor but the theatre’s message itself.

Reza Jafari, Holy War, 2017, Aachen. Photo Martin Von Hehn.

Holy War (جنگ مقدس, 2017) is one of the recent works of the Chaos Theatre. It is an adaptation from Another World. In this book, based on her research on Guantánamo prison, writer Gillian Slovo created an interview-driven account of the Islamic State’s practices and its appeal to young Europeans. Jafari’s adaptation is the story of three teenagers living in Germany who join the terrorist group of the Islamic State (ISIS). Also, a Yazidi woman narrates her experiences of captivity by ISIS’s and her frequent sexual assault (a rape scene is shown by a dance sequence.). The narrators are all women; the mothers who have experienced their children’s move from a democratic country (Germany) to the ISIS’s camp. Jafari has always tried to highlight the role of women in his plays, in reaction to the practices in his country of origin, where women have always been discriminated against.

Another recent play by this company is an adaptation of Heinrich Böll’s The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum (آبروی از دسترفتهی کاترینا بلوم, 2018). A divorced woman is arrested after a meeting with a man because he is a member of an outlawed group and the police are in search of him. Throughout the interrogation, the police, in collaboration with the prosecutor, are busy exploring the innermost aspects of the woman’s life. Meanwhile, the newspapers also play a huge role in making Katharina appear guilty in the public opinion. The story takes place in Germany in 1974, the period of the activities of the Baader-Meinhof Group or the Red Army Faction. In this play, Jafari adds a new personage to the story of Heinrich Böll: an elderly man sitting quietly during many of the scenes, listening carefully and notes. In the middle of the play, the spectator is informed that he is the father of Katarina. In the scene when Katarina is sitting in the corner of her cell, she performs some songs, all based on poems written by Reza and then translated into German.

Reza Jafari, The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, 2018, Aachen. Photo: Martin Von Hehn.

Reza Jafari’s adaptation is relevant not only to events in 1974 Germany but also to issues in Iran today. Referring to the suicide of several prisoners in Iran’s jails during the recent protests (January 2018), Jafari says: “These are lies that are given through Iranian media to the people, which is one of my reasons for choosing this text.” [17] He always tries to relate the text to his own country, because one of the most significant problems in Iran is censorship, linked to violence and the defamation of human rights. Jafari is often inspired by Brecht’s Alienation Effect. Thus, the German spectator realizes something that cannot be seen in other theatres, and that is the references to Iranian culture which the director of Chaos Theatre presents.

For Reza Jafari this is “the smallest thing he can do for his compatriots to prove that, although he has been in exile for 30 years, but his culture has not gone away.”[18] He believes in the theatre and in human beings. He states that, as long as the Islamic Republic is in power, he will never be able to perform his works in Iran, because, “In my opinion, the biggest insult to an exiled artist living in Europe, is to ask his actress to wear a scarf over her head. This is a direct insult to the woman and to me, and a great example of censorship.”[19]

Soheil Parsa

Using the concept of “empty space,” minimalist staging, emphasis on the pure presence of the actor as the main element of the theater, semantic lighting, representation of Iranian texts in English inspired by western theatre techniques, in another word, a cultural blend, are some of the features of Modern Times, an interdisciplinary theatre company formed in 1989 by Soheil Parsa and Peter Farbridge.

How to eliminate violence? How can we see the power of cultural roots? And how can a nation overcome its history and seek to cure its suffering? These are some questions that Parsa’s works try to answer. What is attractive in Parsa’s creation is the fluidity and the blending of interdisciplinary elements. His theater addresses its social, political and cultural concerns not in slogans or propaganda, but in a very quiet and effective context: it is a theatre that participates as an interventionist. This intervention reflects the cultural boom of Parsa: an image of the multicultural nature of his motherland (Iran) as well as the cultural diversity of his host country (Canada). Parsa’s theatre could be considered as interventionist because, like the works of William Kentridge, a South-African director, they “are full of engagement with the committed discourse, and no direct personal expression or a particular political obligation.”[20] In another word, his works are not only a set of interdisciplinary techniques (for purely aesthetic purposes) but also a reflection of the reality that reveals the experiences of Parsa as an émigré.

Soheil Parsa, Hallaj, 2011, Toronto. Photo: John Lauener.

In his play, Hallaj (2011), which had a major difference from the historical personage, Farbridge played the role of Hallaj, a Western white man with contemporary clothing. In addition, the issue of Hallaj’s migration is similar to the current situation. The historic Hallaj was born in Iran and traveled from Mecca to the Far East, where he was introduced to Buddhist teachings; finally, he reached Baghdad when he was about sixty-years-old and sentenced to death. However, in this production, Hallaj is a young man and not very much involved in mystical or spiritual affairs. He has maybe one point in common with the famous Hallaj: no fear of death. This could be interpreted as a sign of faith, like an exile who tries to find a better and free life and has no fear even of death. Hallaj was presented in the form of flashbacks to his life; he is a traveler who to one critic seemed “like a cross between Jesus and Gandhi.”[21]

Shahrokh Moshkin Ghalam

Though the art of dance has existed alongside the theatre as one of the oldest arts in the world, the dance-theatre (professionally) culminated in the twentieth century with the formation of German Expressionism. Among the most prominent artists in this field are the German Pina Bausch and French Maguy Marin, whose works fluctuate between dance and theatre. The dance-theatre is an artistic mix. It is dance because its language is music and its significance obtained through the rhythmic range of the muscles; while at the same time it is theatre, because it has both a formulation of personage and some dramatic situations. This interdisciplinary combination provides a great opportunity for its creator. He/she can convey the ideas to the audience without verbal dialogues and only through body language. Most of Shahrokh Moshkin-Ghalam’s works are influenced by interdisciplinary viewpoints. An example is the performance of Sohrab and Gordafarid (سهراب و گردآفرید) (2009), which was created with two personages. The dancers’ bodies were semi-topless and attracted the audience to its movements. There was a blend of flamenco dance, inherently matched with men’s energy, as well as the mechanical movements of Baris dance also traditionally performed by men. These actions make an allusion to the battle of Sohrab and the travesty Gordafarid, who tried to defend her territory. The performance, regardless of its Persian references, could communicate with every audience because the verbal language lost its prominence and the meanings were transferred through dance.

Shahrokh Moshkin Ghalam, Sohrab and Gordafarid, 2009.

Dance can be a resilient art because it moves toward life. All the movements of the dancer are based on her/his resistance to stagnation. Now, this physical struggle can become a politico-social expression in the context of Iranian culture. For present-day Iran, women’s dancing is forbidden and in traditional Iran, men’s dancing was considered unconventional, Moshkin-Ghalam’s choreographies create resistance against both. Moreover, his body is a mixture of different cultures; it is also an exiled body because it cannot perform in his homeland.

Conclusion

The study of theatre in exile can open a new horizon in cultural and political studies. It is also a worthy opportunity to understand the interdisciplinary phenomena that have grown considerably in contemporary art. To analyze works in exile means to study the multicultural identity of the artist. Likewise, these works can be highly biased and engaged in propaganda, or at the same time as they achieve their enlightening commitment (which is not necessarily political), they can also remain loyal to the political commitment (which is not dogmatic but more critical). To accomplish this goal, the adaptation of classical texts and their updating in the interdisciplinary context is a very appropriate and influential approach. The artists mentioned in this essay have each succeeded in some way in advancing this goal; they have been able to apply theatre as an interventional factor. They seek to demonstrate that they are still alive and involved in the process of creation. What seems important is to “show the moon to the audience.”

Sepideh Shokri Poori is a Ph.D. Candidate in Theatre Studies and Performing Arts at Laval University (Quebec, Canada). Since January 2015, she has been preparing her thesis under the direction of Dr. Liviu Dospinescu, associate professor at Laval University. Her dissertation is entitled “Iranian theatre as Means of Intervention in post-revolutionary years (1979- ).” She has published critical articles (Both in French and English) in the field (“Iranian Theatre as Means of Intervention: The Intercultural discoures in Hey! Macbeth, only the first dog knows why it is barking!”) and translated theoretical books and plays, including Reading Theatre by Anne Ubersfeld, S/Z by Roland Barthes, Serendipities by Umberto Eco, and Situation Vacant by Michel Vinaver. She is now a researcher in SeFeA Theatre Laboratory, at Sorbonne-Nouvelle University (Paris 3, France). Shokri has artistic experience (author and dramaturg) often inspired by her research interests.

[1] Georges Banu, La scène surveillée: essai, Arles, Actes Sud, 2006, p. 7, (« Le temps du théâtre »).

[2] The Shahnameh, also transliterated as Book of the Kings is a long epic poem written by the Persian poet Ferdowsi between c. 977 and 1010 CE and is the national epic of Greater Iran.

[3] Yannis Kiourtsakis, “Patrie, exil, nostos,” Sens Public, March 3, 2012, http://www.sens-public.org/article920.html. Accessed February 9, 2018.

[4] Marie-Claude Hubert, Les grandes théories du théâtre (Paris: ARMAND COLIN, 2010), 23. Author’s translation.

[5] Bertolt Brecht, Dialogues d’exilés: Suivi de Fragments (Paris: L’ARCHE, 2006), 3.

[6] Ibid., 9.

[7] Samuel Beckett, L’innommable, (Paris, Les éditions de Minuit: 2015), 160.

[8] Umberto Eco, Serendipities: language et lunacy, (New York, Columbia Univ. Press: 2014), 39.

[9] Jacqueline Amati-Mehler, “La migration, la perte et la mémoire,” Ela. Études de linguistique appliquée no 131, no. 3 (2003): 329–42.

[10] vista.ir, « مرور کارنامه سوسن تسلیمی در گفتگو با خودش / 320198 », [En ligne : http://vista.ir/article/320198]. Consulté le25 février 2018.

[11] “Un vrai masque ne cache pas, il rend visible,” https://www.theatre-du-soleil.fr/fr/a-lire/un-vrai-masque-ne-cache-pas-il-rend-visible-4147. Accessed April 30, 2018.

[12] «Les dits parfumés d’Hamid Reza Javdan», interviewed by Patrick Navaï, Paris, P.2.

[13] Ibid., 4.

[14] Yoshi Oïda, The Invisible Actor, (New York, Routledge: 1997), Preface, Viii.

[15] Patrice Pavis, Theatre at the Crossroads of Culture, (London; New York: Routledge, 1992), 4.

[16] Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com), « جنگ مقدس؛ روایت گریز جوانان از دامن دموکراسی به دام داعش | DW | 12.06.2017 », http://www.dw.com/fa-ir/. Accessed April 29, 2018.

[17] Deutsche Welle (www.dw.com), « هاینریش بل با نشانههایی از فرهنگ ایرانی بر صحنه تئاتر آخن | DW | 04.03.2018 », http://www.dw.com/fa-ir/. Accessed April 29, 2018.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Liviu Dospinescu, « Vers un nouveau théâtre politique: William Kentridge et les discours transculturels ».

[21] J. Kelly Nestruck, “Only a Perfect Martyr Mars the Beautiful Tale of Hallaj,” https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/theatre-and-performance/only-a-perfect-martyr-mars-the-beautiful-tale-of-hallaj/article630113/. Accessed April 10, 2016.

___________________________________________________

Arab Stages

Volume 8 (Spring 2018)

©2018 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications

Founders: Marvin Carlson and Frank Hentschker

Editor-in-Chief: Marvin Carlson

Editorial and Advisory Board: Fawzia Afzal-Khan, Dina Amin, Khalid Amine, Hazem Azmy, Dalia Basiouny, Katherine Donovan, Masud Hamdan, Sameh Hanna, Rolf C. Hemke, Katherine Hennessey, Areeg Ibrahim, Jamil Khoury, Dominika Laster, Margaret Litvin, Rebekah Maggor, Safi Mahfouz, Robert Myers, Michael Malek Naijar, Hala Nassar, George Potter, Juan Recondo, Nada Saab, Asaad Al-Saleh, Torange Yeghiazarian, Edward Ziter.

Managing Editor: Ruijiao Dong

Assistant Managing Editor: Alexandra Viteri Arturo

Table of Contents

Essays

- Theatre Elsewhere: The Dialogues of Alterity by Sepideh Shokri Poori

- Contemporary Arab Diasporic Plays and Productions in Europe and the United States by Marvin Carlson

- On Ajoka: An Interview and In Memoriam by Fawzia Afzal Khan

Reviews

- A Space to Meet and Share: A Corner in the World Fest 3 from Istanbul by Eylem Ejder

- The Wind in the Willows Makes It to KSA by Areeg Ibrahim

- Documentary Theatre in Egypt: Devising a New Play in Cairo by Jillian Campana and Sara Seif

- Boundaries of History, Memory and Invention: Laila Soliman’s ZigZig in Light of Absence of Egyptians’ Right to Freedom under Information Law by Hadia abd el-fattah Ahmed

- The Yacoubian Building Onstage: An Interview with Kareem Fahmy by Catherine Coray

- Theatre Everywhere: How A Small Lebanese Village Transformed for Blood Wedding By Ashley Marinaccio

Plays

- The Unfaithful Husband by James Sanua (Ya`qub Sanua), translated by Marvin Carlson and Stefano Boselli

- Secrets of a Suicide by Tawfia al-Hakim, translated by Maha Swelem

- A Knock from the Stork by Mostafa Shoul

www.arabstages.org

[email protected]

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director