The US-led invasion of Iraq in March, 2003, and ensuing occupation, was seen by some Iraqis, initially, as an act of liberation from the brutal dictator Saddam Hussein. Such enthusiasm, however, was quickly dampened as the allied forces were ill-equipped to maintain order. Two events in particular, which occurred during the early months of the occupation, were held up as evidence by those who wished to dispute America’s professed good intentions. The first of these was the widespread looting and vandalism that broke out in Baghdad in the weeks following the invasion, with an emphasis on the assault on the Iraq National Museum. The second was the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, which was made public in April, 2004, 13 months into the occupation. As the first of these occurred, US forces stood by, lacking a mandate from their military command to intervene. Some Iraqis even held the Americans responsible for actively participating in the looting, despite lacking evidence for this claim. Critics of the invasion, in Iraq and indeed across the Arab world, compared the assault on the museum and city at large to the Mongolian razing of Baghdad during the thirteenth century. The Mongolian ruler Hulagu destroyed the city, which was at that time the capital of the Islamic caliphate, and massacred its inhabitants, bringing an end to the Islamic Golden Age. In this comparison, the US figures as an imperialistic, malignant force, eager to destroy a people and culture which it views as inferior. The Abu Ghraib torture scandal only reinforced this image. Photographs taken by American soldiers captured the torture and humiliation of Iraqi detainees in graphic detail. These two events, taken together, provided proof enough, for many in the Arab world, of the bad intentions of the US and its allies.

Writing in response to the invasion, a number of Iraqi playwrights have utilized one or both of these events to depict the incursion as an assault on both the Iraqi people and their cultural heritage. It is noteworthy that the Iraqi national identity is at least partially built upon the nation’s pride in its territory being roughly coterminous with that of ancient Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization. The attack on the museum served to reinforce the conviction that the foreign troops were intent on desecrating Iraq’s cultural heritage. Examples of Iraqi plays that invoke Abu Ghraib and/or the Mongolian invasion include Abbas Abdul Ghani’s Barbed Wire (2008), Sabah al‑Anbari’s Lust of the Ends (2007), and Rasha Fadhil’s Ishtar in Baghdad (2004). In the first of these, a character laments that the Americans did more damage to Baghdad than the Mongolians did. In Lust of the Ends, the protagonist witnesses American troops vandalizing the Iraq National Museum as well as the Iraq National Library and Archive, reinforcing the false claim that Americans were directly responsible for the damage. Additionally, the Mesopotamian deity Tammuz describes, in poetic language, the darkening of the waters of the Tigris, stained with the blood of Hulagu’s victims and the ink of books pillaged from Baghdad’s renowned libraries, using imagery that is well-known to Iraqis. In another episode, the protagonist witnesses the degradation of Iraqi detainees at Abu Ghraib.

Rasha Fadhil, Beirut, Feb. 2018. Photo Credit: Rasha Fadhil.

What is unique about the third play, Ishtar in Baghdad, however, is that Fadhil introduces Mesopotamian deities into war-ravaged Baghdad as characters who not only witness the destruction of the city and the assault on its inhabitants, but themselves are apprehended by American troops and tortured by them. Rather than depicting the destruction of artifacts, as symbols of her country’s cultural heritage, she brings that heritage to life, so to speak. As the protagonists are fertility gods, tied to cycles of death and rebirth, this facilitates her characterization of the Iraqi people as resilient since she implies that, like the gods, they will be restored to their former glory in good time. In what follows, we will chart Fadhil’s development of the mythology of these two figures as representative of the Iraqi psyche in the face of the invasion and, specifically, the Abu Ghraib torture scandal. We will link the deities’ promise of rebirth, which occurs at the conclusion of the play, to the concept of sumud, or “steadfastness,” as an attribute of the Iraqi character. In this way, the dramatist deploys Iraq’s ancient heritage as cultural currency.

Fadhil is an award-winning Iraqi writer and activist currently based in Lebanon. She was born and raised in Basra, has a BA in English from the University of Tikrit, and a Certificate in International Journalism and Media Studies from the Institute of Arab Strategy in Beirut. She has published collections of short stories, poetry, and criticism. As an activist, she has been involved in promoting AIDS prevention through health education, working with the Red Crescent and the Red Cross in Iraq. She has received recognition both inside of Iraq and internationally: the Iraqi Ministry of Culture has honored her and she has received international awards in short fiction and playwriting. Her plays have been staged in Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, and Oman, and Ishtar in Baghdad was given a staged reading by a group of students in Australia. It has yet to receive a professional production.

In Ishtar in Baghdad, Fadhil manifests the ancient origins of Iraqi culture. Mesopotamia refers to the region encompassed by the Tigris-Euphrates Valley, which was the site for the world’s first cities, irrigation systems, states and empires, writings, and recorded religions, and accommodated the civilizations of the Sumerians, Akkadians, Babylonians, and Assyrians; excavations have uncovered sites dating back to 7000 B.C.E. Versions of the myth of Ishtar and her consort Tammuz survive from Akkadia and Sumer, and detail journeys to the netherworld in which power is lost and then reclaimed, corresponding to the loss and restoration of fertility. As noted above, the playwright conflates the myth with the Abu Ghraib scandal. The report that aired on CBS included graphic photographs of the torture of Iraqi inmates at a detention center on the site of what had been a notorious prison under the Hussein regime. The photos had been taken in the fall of 2003. The inmates are naked in many of them, placed in humiliating and often sexual positions. In some, American soldiers pose gleefully alongside detainees and even a dead body. The images were distributed worldwide and damaged the image of America as liberator of Iraq. In juxtaposing the myth with the prison scandal, and indirectly referencing the pillaging of the Iraq National Museum, Fadhil depicts the invasion and occupation as an attack upon both the modern-day populace and the ancient heritage of the Iraqi nation.

In the myth, Ishtar, referred to as Inanna in the Sumerian versions, descends to the netherworld in order to add that realm to her domain and claim the power of death and rebirth. Tammuz appears in this narrative but also in his own, parallel ones, in which he as well descends to, and returns from, the netherworld. The liturgies of Damu relate the journey of an aspect of Tammuz, also referred to as Dumuzi, who is associated with the fertility of vegetation. The journey is undertaken in order to fulfill his divine function of granting prosperity, specifically the fertility and rejuvenation of the vegetable kingdom and of the forest, watercourses and marshes. The narratives of Ishtar and Tammuz belong to a group of Sumerian myths of the goddess-and-consort type which often favor the female. In many of them, the male suffers death or disaster and must be rescued by the goddess.

In the Akkadian myth of Ishtar, the netherworld is described as a gloomy place in which

those who enter are deprived of light,

… dust is their food, clay their bread.

They see no light, they dwell in darkness.… (Trans. Stephanie Dalley, Myths from Mesopotamia, Oxford, 1989, 17-18)

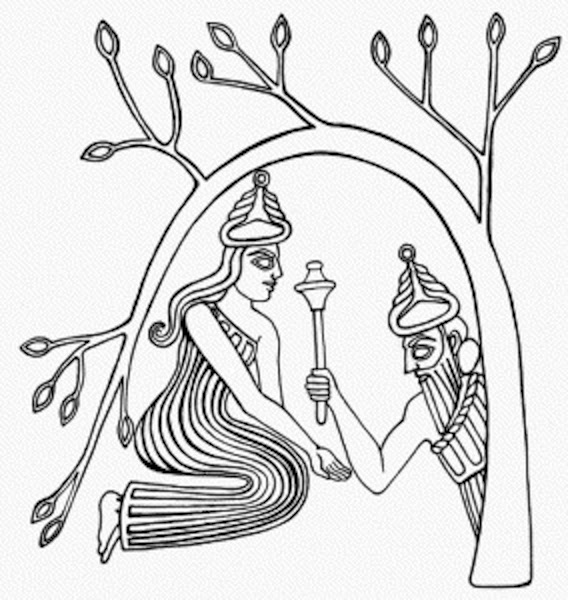

Ishtar descending into the netherworld. Photo Credit: www.bing.com.

In this version, fertility ceases on earth while Ishtar is confined to the netherworld. The goddess is required to surrender her accoutrements and clothing, which correspond to her powers, in stages as she passes through seven gates to arrive naked before Ereshkigal, the queen of the netherworld. Ereshkigal punishes her for her transgression: in the Akkadian version, she commands her minister to release sixty diseases against Ishtar and in the Sumerian version, Ishtar is killed and hung on a hook for three days and nights. A sprinkling of life-giving water and, in some renditions, a meal from the plant of life, revive her. Both Ishtar and Tammuz reclaim their power when they ascend to the overworld, and fertility is restored. The goddess achieves dominion over both realms.

Inanna Dumuzi in the Underworld. Photo Credit: ferrebeekeeper.wordpress.com.

In Fadhil’s play, Ishtar and Tammuz embark on a passage that parallels that described in their mythology. The journey of Ishtar and Tammuz occurs in two phases: first, they visit war-torn Baghdad, and next, they are detained at Abu Ghraib. Horrified by what they are able to ascertain from their perch in a distant realm, the gods descend to earth in order to assist their children, the Iraqi people, and to restore fertility to the land. In Baghdad, they witness an explosion and attempt to assist the victims. They encounter a cross-section of Iraqi civilians affected by the blast: people crying out for help, a girl separated from her friends, a wounded man, a group of boys curious about the explosion, and a woman who lost her son three years ago. The members of this Iraqi chorus, as it were, respond to the explosion in various ways. Some are terrorized by the immediate violence, and others appear to be worn down by sustained conflict. They are confused by the gods’ claims of who they are. Since the word Tammuz, in Arabic, designates the month of July, a wounded man fails to understand Ishtar’s request for help locating her consort after he has disappeared in the crowd. The boys know Sumer only as a brand of cigarettes. The girl separated from her friends has lost her books and frets about missing an examination. The implication is that the other Iraqi characters, as well, have failed an examination about their cultural heritage, which indicates that they have lost track of, or have had torn from them under the duress of warfare, something essential which binds them to the earth.

The most poignant of these characters is the street vendor who has arrayed, on the pavement before her, desserts which she claims to have made for her missing son. She asserts that he disappeared some three years prior in another explosion. Since the boy’s school bag was returned to her, the woman clings to the hope that he is still alive. Having found his math notebooks in the bag, she laments that his instructors failed to teach him that “two minus one equals zero,” an equation that quantifies her grief. She hopes to lure him to her with the sweets and would accept, as payment for them, that he “take [her] with him,” a statement that implies that she would rather join him in death then continue to live without him.

Although initially hostile to Ishtar, the vendor decides to help her, revealing that she saw American soldiers take away Tammuz, and warning Ishtar against pursuing him. Ishtar ignores her advice. Her quest parallels certain versions of the myth, in which the goddess wanders the earth in search of her lover before rescuing him from the netherworld. Sure enough, Ishtar is soon taken into custody by the Americans. The remainder of the play chronicles the second part of the gods’ journey in which they, and their fellow prisoners, suffer abuse at the hands of American soldiers in the netherworld that is the detention center, recalling the enervating disrobing of Ishtar and the violence inflicted upon her by Ereshkigal. The detainees are beaten, subjected to electroshock, forced to dance, put on leashes and ordered to bark like dogs, stacked on top of one another, stripped, and raped. These abuses are primarily derived from those documented in the photos from the Abu Ghraib prison. According to a report issued in 2004 as the result of a military investigation led by Major General Antonio Taguba, abuses committed by American soldiers against Iraqi detainees included:

shooting and beating… acts of sodomy and rape, videotaping and photographing naked male and female detainees, many in sexually explicit postures and forced sexual performances, arranging detainees in human piles and jumping and sitting on them, simulating electrocution, [and] using dogs to intimidate and in some instance injure detainees (Michelle Brown, “The Abu Ghraib Torture and Prisoner Abuse Scandal,” Crimes and Trials of the Century, ed. Steven M. Chermak and Frankie Y. Bailey. Greenwood Publishing, 2007, 306.).

In one image, female soldier Lynndie England keeps a detainee on a dog leash. In her play, Fadhil elaborates on the photographs: soldiers collar detainees on leashes, command them to bark, and order them to ride on each other’s backs. It has been documented elsewhere that Taser stun guns were used on Iraqi detainees. Indeed, the soldiers in Fadhil’s play beat detainees with stun batons and other weapons, and they rape female detainees and deprive both sexes of clothing. A hood is placed over Tammuz’s head and he is forced to stand with his arms spread in a reference to what is perhaps the most iconic photograph, which shows a prisoner in this stance, standing on a box with electrical wires trailing from his hands and neck. The soldiers in the play snap photos from every side. The deeply humiliated male prisoners beg for death. Together naked in a cell, the female prisoners long for death as well, having been shamed, as they report, through the act of rape.

Abu Ghraib torture victim. Photo Credit: Middle East Monitor.

The soldiers are not, however, invincible, and the gods and their people find ways to resist. An officer who beats Ishtar exhausts himself to the point of tears, admitting a sort of defeat as he collapses and orders her taken away. They refuse to believe that Ishtar and Tammuz are gods, and in doing so, it would seem, underestimate the resilience of the Iraqi people and their culture. The gods’ insistence on their divinity in the face of adversity is in itself a form of resistance. One of the naked, female detainees has smuggled a message out to her parents, asking for them to arrange for the prison to be bombed so that the prisoners will be killed and thereby released from their shame and celebrated as martyrs. Her plea is answered as the scene concludes with the sound of explosions, met with cries of joy by the women. Ishtar and Tammuz, finally united in the prison, agree that it is best to die to fulfill the prophecies that they will be reborn.

As noted above, Fadhil equates the thirteenth century Mongolian invasion with the twenty-first century American one, inclusive of the pillaging of the Iraq National Museum. The invasion of Baghdad in 1253 by the Mongolians marked the end of the Islamic Golden Age. The Abbasid Empire, ruled from Baghdad, was renowned for its rich culture and advances in science and the arts; its reign spanned from roughly 750 C.E. up until the Mongolian invasion. Hulagu and his armies killed up to 800,000 of the city’s inhabitants. They destroyed the libraries, architectural treasures and mosques, and looted the Caliph’s treasury. The 2003 looting and pillaging of the Iraq National Museum was perpetrated by Iraqis while American soldiers stood by, as the US command had failed to prepare its troops to counter the civil unrest that followed the invasion. The invasion of Iraq commenced on March 20, 2003; on April 5, American forces entered Baghdad; the looting of the museum took place on April 8-16. The museum is considered the world’s main repository for the archaeological treasures of ancient Mesopotamia. Although the American military has been charged, in the Western press and by its own account as reported by Major General Taguba, with insufficiently protecting the library and archive, Iraqis who stormed the institutions appear to be responsible for the actual damage. Rumors to the contrary, possibly spread by Baathist loyalists, directly blame the Americans. Fadhil has, in effect, brought the culture represented by the looted artifacts to life through the characters of Ishtar and Tammuz as signifiers of Mesopotamian antiquity, savaged in the play by American soldiers.

The Diez Albums, Fall of Baghdad. Photo Credit: history.msu.edu.

Although the Iraqis in earlier scenes are ignorant of, and therefore disconnected from, their heritage, by the conclusion, the prisoners are, as it were, empowered by the proximity to the gods. As sounds of joy, howling, guns, and explosions shake the stage, the Americans flee in confusion and the prisoners rise up in celebration. Eventually the noise dies down and the only sound is that of the rumble of the rain. In Arabic culture, rain is a complex symbol but it may, under certain circumstances, connote revolution. In the myth, Ishtar is revived by a sprinkling of water. The surrendering of the gods and the detainees to death with the promise of rebirth, combined with the sound of rain, suggests that resurgence is inevitable. Ishtar and Tammuz are, after all, fertility gods whose journeys are synchronous with that of the earth around the sun; after winter comes the spring. Resurgence is best read broadly here, as that of the Iraqi people as a whole rather than as a sectarian uprising, since the playwright refrains from highlighting divisions between Iraqis, and focuses, rather, on the impact of American intervention.

The play would seem to suggest that Iraqis will find strength in reconnecting with their ancient cultural heritage in the face of a barbarism visited upon them by an impertinent, imperialist America. This strength is tied to the soil itself: in the opening scene, Ishtar promises Tammuz, “I want you to observe how greenness pushes back the tide of blood.” The land itself will grant strength to its long-term inhabitants. Indeed, Hussein’s regime promoted “steadfastness” (sumud) as an aspect of Iraqi national consciousness as he led the country through a series of disasters, and sought to depict himself as the inheritor of Mesopotamian greatness. According to Eric Davis in his 2005 study of Iraq, Memories of State, Hussein’s Baathist state constructed an “historical memory” that “focused primarily on the premodern era, especially the ‘Abbasid Empire, ancient Mesopotamia, and Arab society during the al-Jahiliya or pre-Islamic period’ (4). Although Hussein was toppled from his lofty perch and executed, and the darker side of his regime has been shown by other Iraqi dramatists like Jawad Al-Assadi, Fadhil suggests a more enduring aspect of Iraqi culture, rooting it in an ancient past. She advances the notion that the Iraqi nation will outlast the passing cruelty of foreign invaders and one day recover the splendor of ancient Mesopotamia.

[1] Special thanks to Reza Mirsajadi for co-chairing the working session, “Arousing Activism: Revolutionary Impulses in Middle East Performance,” at the American Society for Theatre Research Annual Conference in 2018, at which an earlier draft of this article was workshopped. We are grateful to Marjan Moosavi for her feedback at this forum. (Although the conference was canceled, the working session convened online.) Some of the material in this article is adapted from Amir Al-Azraki’s dissertation, Clash of the Barbarians: The Representation of Political Violence in Contemporary English and Arabic Language Plays about Iraq (York University, 2011).

Amir Al-Azraki is an Assistant Professor of Arabic language, literature, and culture (Renison University College, University of Waterloo). He received his BA in English from the University of Basra, his MA in English literature from Baghdad University and his PhD in Theatre Studies from York University in Toronto, Canada. He is a Theatre of the Oppressed practitioner and playwright who works across cultures to highlight and facilitate discourse and interchange through his work. His projects in Applied Theatre have been employed in workshops throughout Canada, USA, and Iraq. He has worked with women artists, students, and refugees, utilizing Theatre of the Oppressed techniques to address human rights issues. Among his plays are: Waiting for Gilgamesh: Scenes from Iraq, Stuck, The Mug, and The Widow. Al-Azraki is the co-editor and co-translator of Contemporary Plays from Iraq.

James Al-Shamma is an Associate Professor of Theatre at Belmont University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he teaches theatre history and literature, and scriptwriting. He is coeditor and co-translator of the anthology Contemporary Plays from Iraq (Methuen) and is the author of Sarah Ruhl: A Critical Study of the Plays and Ruhl in an Hour. He is a cofounder of Verge Theatre Company and most recently directed their coproduction, with Belmont University, of Sarah Ruhl’s adaptation of Chekhov’s Three Sisters. He earned his PhD in Dramatic Art at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Arab Stages

Volume 10 (Spring 2019)

©2019 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center Publications

Founders: Marvin Carlson and Frank Hentschker

Editor-in-Chief: Marvin Carlson

Editorial and Advisory Board: Fawzia Afzal-Khan, Dina Amin, Khalid Amine, Hazem Azmy, Dalia Basiouny, Katherine Donovan, Masud Hamdan, Sameh Hanna, Rolf C. Hemke, Katherine Hennessey, Areeg Ibrahim, Jamil Khoury, Dominika Laster, Margaret Litvin, Rebekah Maggor, Safi Mahfouz, Robert Myers, Michael Malek Naijar, Hala Nassar, George Potter, Juan Recondo, Nada Saab, Asaad Al-Saleh, Torange Yeghiazarian, Edward Ziter.

Managing Editor: Maria Litvan

Assistant Managing Editor: Joanna Gurin

Table of Contents:

PART 1: Toward Arab Dramaturgies Conference

- A Step Towards Arab Dramaturgies by Salma S. Zohdi

- A New Dramaturgical Model at AUB by Robert Myers.

- Dancing the Self: A Dance of Resistance from the MENA by Eman Mostafa Antar.

- Traversing through the Siege: The Role of movement and memory in performing cultural resistance by Rashi Mishra.

- The Politics of Presenting Arabs on American Stages in a Time of War by Betty Shamieh.

- Towards a Crosspollination Dramaturgical Approach: Blood Wedding and No Demand No Supply by Sahar Assaf.

- Contentious Dramaturgies in the countries of the Arab Spring (The Case of Morocco) by Khalid Amine.

- Arab Dramaturgies on the European Stage: Liwaa Yazji’s Goats (Royal Court Theatre, 2017) and Mohammad Al Attar’s The Factory (PACT Zollverein, 2018) by Sarah Youssef.

PART 2: Other

- Arabs and Muslims on Stage: Can We Unpack Our Baggage? by Yussef El Guindi.

- Iraq’s Ancient Past as Cultural Currency in Rasha Fadhil’s Ishtar in Baghdad by Amir Al-Azraki.

- Amal Means Incurable Hope: An Interview with Rahaf Fasheh on Directing Tales of A City by the Sea at the University of Toronto by Marjan Moosavi.

- Time Interrupted in Hannah Khalil’s Scenes from 71* Years by Kari Barclay.

- Ola Johansson and Johanna Wallin, eds. The Freedom Theatre: Performing Cultural Resistance in Palestine. New Delhi: LeftWord Books, 2018. Pp. 417 by Rebekah Maggor.

www.arabstages.org

[email protected]

Martin E. Segal Theatre Center

Frank Hentschker, Executive Director

Marvin Carlson, Director of Publications

Rebecca Sheahan, Managing Director

Arab Stages is a publication of the Martin E. Segal Theatre Center ©2019

ISSN 2376-1148